The idea of a metafilm has resulted in some brilliant innovations over the years, with plenty of pretentious cinematic offerings to follow. Simply meaning ‘self referencing’ or ‘self-reflective’, meta can apply to many things in the world, though when a filmmaker goes meta, the potential for genius is right at hand. No genre has arguably gotten the most mileage out of this idea than horror. For all its merits, there are plenty of well-trodden conventions to pick at with horror, particularly across the slasher realm where by the mid 80s the cheap-and-cheerful trend had become a by-the-numbers slog, begging to be re-evaluated and poked fun at in the process. There is a fine art to a good meta horror film, though for every Scream there is of course a Scary Movie which, while self-referential (and often hilarious), has stretched beyond meta into parody. This list tries to keep it close, though comedies are by no means excepted.

8 Meta Horror Movies That Define the Genre

From 90’s dream slashers to Whedon’s meta horror masterpiece these 8 meta horror films are perfect examples of what can be done in meta horror.

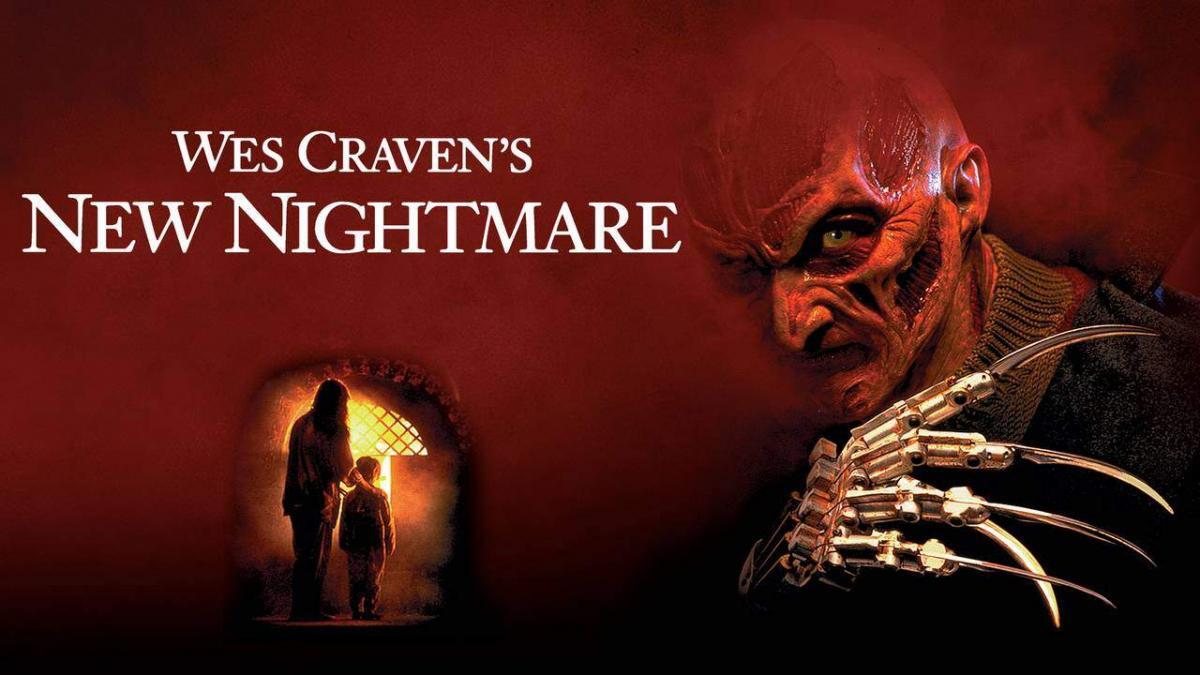

Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994)

Picture it; you’re six films deep into the A Nightmare on Elm Street series and you’re sure Freddy Krueger is gone for good. Then horror maestro Wes Craven decides to up the ante with one of the more original twists on any established horror franchise, and brings Freddy into the real world.

Set apart from other films in the series, New Nightmare portrays Krueger as a fictional villain who begins to terrorize the ‘real-life’ Heather Langenkamp, who played Nancy Thompson from the original series. Heather is plagued by her history working on the Elm Street series, experiencing nightmares, menacing phone calls and traumatic episodes involving her son Dylan. When her husband is killed by mysterious claw marks, she suspects that Freddy himself has found a way into the real world. She visits recognizable figures such as Robert Englund and Wes Craven to try and get to the bottom of the horrific events.

Taking this kind of leap with an established horror villain was bold to say the least. The result could have been an overly campy, self-parodying mess by all accounts, however Craven knew just how to keep things sinister. Robert Englund’s Freddy is far more menacing this time around, swapping goofy lines and comedic runaround for focused and evil kills, while his signature smirk lets you know you’re still watching a Krueger flick, just an altogether nastier one.

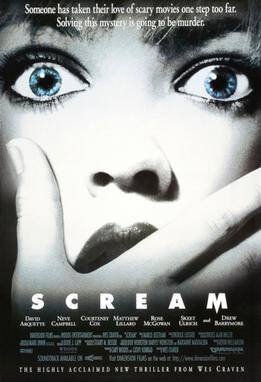

Scream (1996)

If New Nightmare was Craven’s warm-up into meta-commentary, then Scream was both his sharp jab at, and celebration of, the entire horror genre. The film that arguably kicked off a whole generation of parodic comedy with the reactionary Scary Movie series, Scream was Craven taking his self-aware buzz to the next level with a brand new property that would become a long running blockbuster series itself.

Scream gave a whole new generation of horror fans something to revere. While some had the likes of Psycho or Halloween to call their generation’s own, now the 90s had Scream. Taking a simple slasher formula involving a group of college teens being picked off by a masked killer, Craven takes every opportunity to flip each slasher trope on its head, all while having his characters spend much of the film discussing the exact tropes he explores. They describe the rules to surviving a horror film while their friends break each rule and are picked off around them. With a very human-feeling villain, an iconic mask, and some stellar performances, Scream manages to be not only a worthy entry into the slasher genre but an intelligent reevaluation of it and a worldwide classic in its own right.

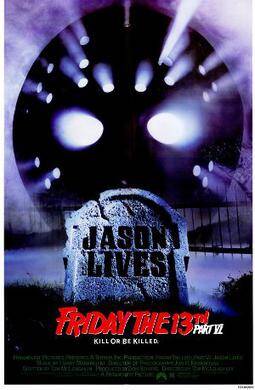

Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives (1986)

This was the point where Director Tom McLoughlin took a good look at the Friday 13th series’ strengths, realised why it was becoming stale and decided to take a less serious, though far more enjoyable approach. The film starts with Tommy Jarvis (Thom Mathews) exhuming Jason’s body to cremate it, in the fear that the maniacal masked killer would arise once more. After impaling the corpse with a metal rod in a fit of rage, the rod is struck with lightning and Tommy’s worst fears are realised.

Jason Lives features the best kills, one of the more likeable casts and more comedy than any other film in the series, and the result is a looser and more exciting affair. With the series’ unexpected, yet greatly effective foray into comedy came constant winks at slasher tropes and jokes like the James Bond gun-barrel opening to Bob Larkin as the graveyard’s groundskeeper, breaking the fourth wall to reprimand the audience for their blood lust. “Why’d they have to go and dig up Jason?” he exclaims directly at the camera. “Some folks have a strange idea of entertainment.”

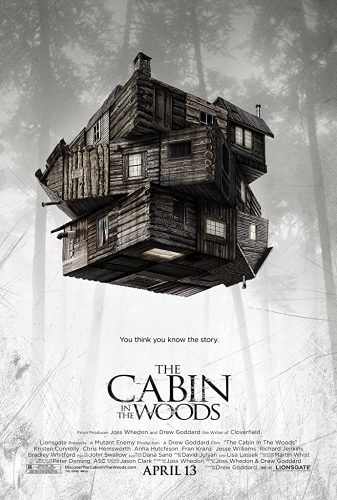

The Cabin in the Woods (2011)

Written by Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard, and directed by Goddard as his directorial debut, The Cabin in The Woods knocks things up a major notch on the meta-scale by showing awareness of all other horror franchises and attempting to build a lore involving all of them. Created as a commentary on ‘torture-porn’ and popular cabin-based horror outings, the film follows five college students travelling to a recognizably rickety old cabin for a retreat. Instead of shrouding the events in mystery, Whedon and Goddard waste no time in showing us a secret underground facility whose occupants are heavily involved with some unknown ritual. The relation between the cabin and the jarringly juxtaposed technicians of the facility is what truly elevates The Cabin in The Woods from comedy slasher to something far more clever and unique. Comedy elements help elevate the meta-slasher plotline and lean more towards wit than slapstick which avoids the film feeling silly or parodical. Goddard runs through each slasher trope, gleefully providing clever insights into how they would work if engineered by some unseen corporate entity. With a competent and often hilarious cast, top quality CG and practical effects and one of the coolest scenes to ever involve a ‘purge system’ button, The Cabin in The Woods is a meta slasher that even the most discerning horror fans can get behind.

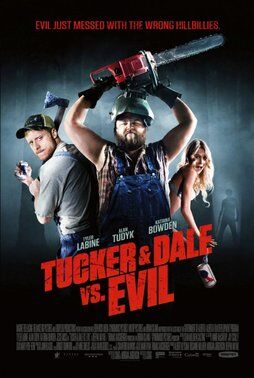

Tucker and Dale vs Evil (2010)

While Tucker and Dale is, on its surface, a classic horror-comedy complete with bloody slapstick and hilarious banter from its leads, it is also a sharp deconstruction of the slasher genre, employing a ‘what if’ edge to classic tropes in a similar fashion to TCITW. Highly subversive and knowledgeable in its source material, Tucker and Dale vs Evil plays with the idea of ‘what if those menacing hillbillies were actually really sweet?’, borderline parodying films like Wrong Turn and Hatchet. Full of hilarious misunderstandings leading to violent consequences, Tucker and Dale manages much of its runtime without an actual established villain in place. Thankfully vacuous-teen-fodder coupled with a wholly lovable pair of lead characters make the entire ride a blast.

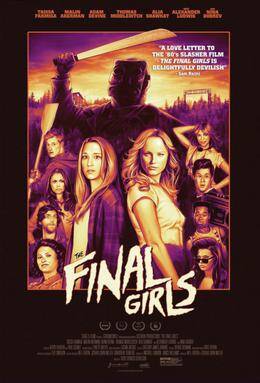

The Final Girls (2015)

The Final Girls plays out like the daydream of a horror-obsessed teen, though something in the sincerity of its execution really works. Recently orphaned Max heads to the cinema with her friends to see a horror flick her mother starred in in the 80s. When the group are sucked into the film and find themselves trapped in its horrific world, they must use all of their wits and knowledge of the genre to survive. Taissa Farmiga does a brilliant job of portraying the grieving and confused Max Cartwright who must reunite with a version of her late mother and come to terms with her realities before it is too late. With plenty of light-hearted jabs at 80s slashers, along with comical performances by the likes of Adam Devine and Thomas Middleditch undercutting the heavier themes on show, The Final Girls is a fun meta slasher idea executed with razor precision and gleeful energy.

Resolution (2012)

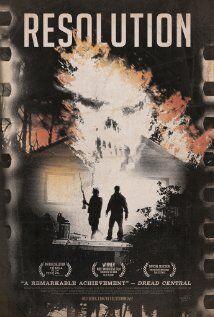

Every film Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead make seems to be layered in more self-awareness than one viewer knows what to do with, though their most committed and playful experiment into meta horror filmmaking is by far 2012’s Resolution.

Chris is a drug addict living in a dilapidated shack in the woods. One day his old friend Michael turns up and, deciding to cure Chris of his addiction, handcuffs him to a radiator. From here, viewers with a wide knowledge of horror stories will be mentally skimming their back-catalogues for some idea of what is about to take place. Very few will get anywhere close.

Without spoiling too much, Resolution has one of the more interesting stories of any horror film in that it creates something of a ‘metanarrative’ in itself, meaning that the plot taking place actually becomes sentient and even a character within itself. While variables are thrown into the mix, such as a couple of drug dealers looking for owed money, the plot eventually inverts on itself and boils down to a story’s purest form, as if Charlie Kaufman himself had directed, albeit with a little more restraint.

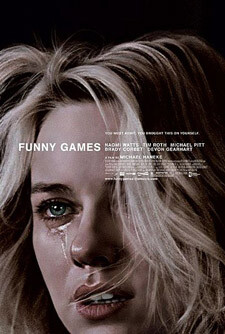

Funny Games (1997/2007)

Michael Haneke’s 2007 remake of his harrowing 1997 horror/thriller Funny Games is not only one of the most disturbing films ever made, but is also boldly and unabashedly meta. Haneke was bored with the excessive violence he saw in the media and so set about making a brutally violent and otherwise rather pointless film of a family being terrorised by two unassuming men. The film is a commentary on Hollywood’s dependence on gore, featuring several fourth-wall breaks from its two lead antagonists, questions as to why the events are even taking place and an ending that throws the viewers entire experience back in their face. With stark realism and phenomenal acting, particularly from Tim Roth and Niomi Watts as the protective parents, Funny games is to this day a unique cinematic experience, and it is recommended you watch both original and remake.

Joe first knew he wanted to write in year six after plaguing his teacher’s dreams with a harrowing story of World War prisoners and an insidious ‘book of the dead’. Clearly infatuated with horror, and wearing his influences on his sleeve, he dabbled in some smaller pieces before starting work on his condensed sci-fi epic, System Reset in 2013.Once this was published he began work on many smaller horror stories and poems in bid to harness and connect with his own fears and passions and build on his craft.

Joe is obsessed with atmosphere and aesthetic, big concepts and even bigger senses of scale, feeding on cosmic horror of the deep sea and vastness of space and the emotions these can invoke. His main fixes within the dark arts include horror films, extreme metal music and the bleakest of poetry and science fiction literature.

He holds a deep respect for plot, creative flow and the context of art, and hopes to forge deeper connections between them around filmmakers dabbling in the dark and macabre.