Knives.

‘Madam?’

Everywhere, knives.

‘Are you all right?’

Knives in the eyes of every onlooker, each glance carving red-hot rivulets of pain through her flesh.

‘You’ll need your ticket.’

Everywhere, knives; everywhere, eyes.

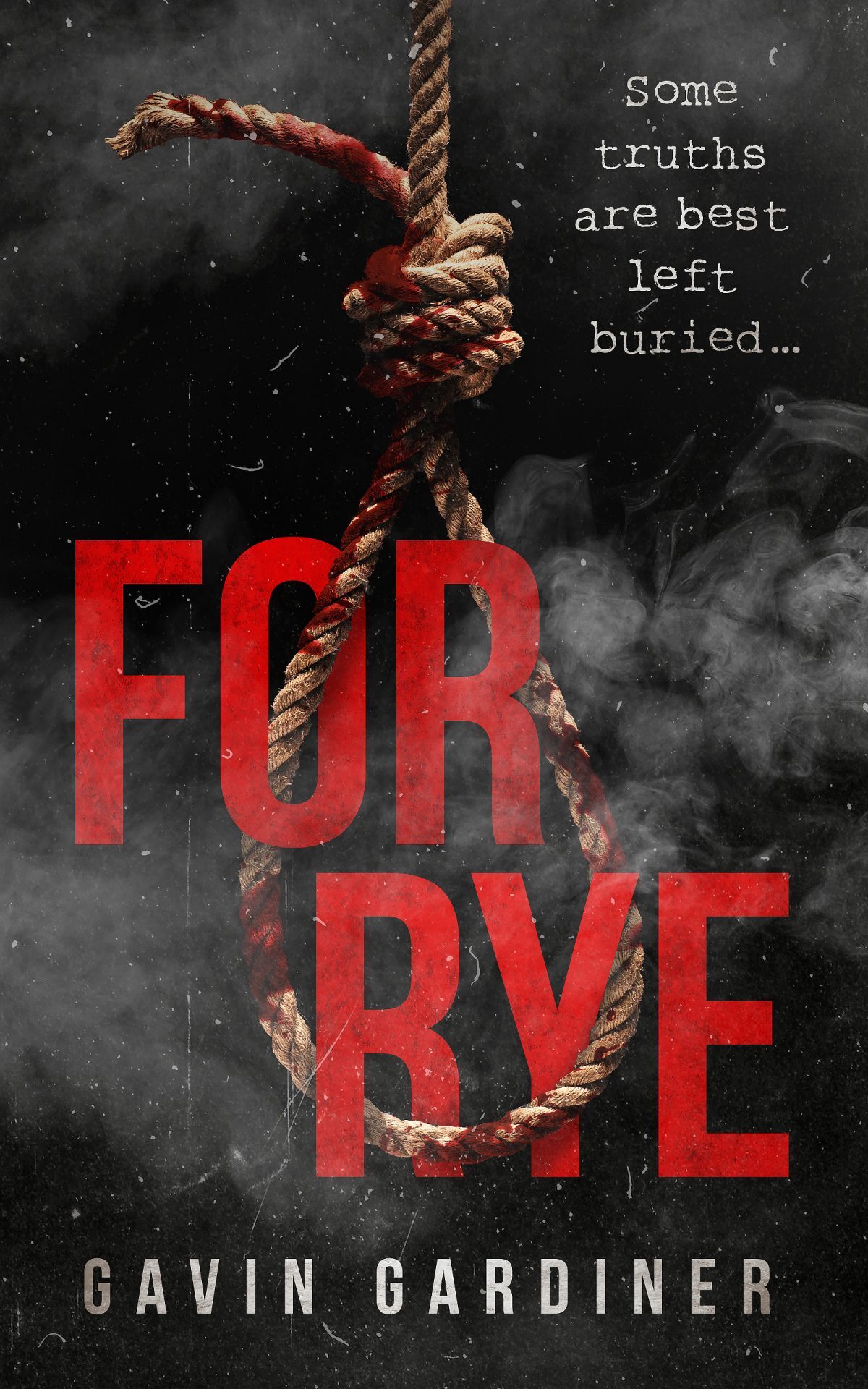

She plunged trembling fingers into her worn leather satchel. Damned thing must be in here somewhere, she thought in the moment before her bag fell to the concrete flooring of Stonemount Central. The ticket collector’s eyes converged with her own upon the sacred square slip, tangled amongst the only other occupant of the fallen satchel: a coil of hemp rope.

They stared at the noose.

The moment lingered like an uninvited ghost. The woman fumbled the rope back into the bag and sprang to her feet, before shoving the ticket into his hand, grabbing her small suitcase, and lurching into the knives, into the eyes.

The crowd knocked past. A flickering departure board passed overhead as she wrestled through the profusion of faces, every eye a poised blade. The stare of a school uniformed boy trailing by his mother’s hand fell upon her, boiling water on skin. She jerked back, failing to contain a shriek of pain. Swarms of eyes turned to look. The boy sniggered. She pulled her duffle coat tight and pushed onward.

The hordes obscured her line of sight; the exit had to be nearby, somewhere through these eyes of agony. She prayed the detective – no, no more praying – she hoped the detective would be waiting outside to drive her, as promised. One last leg of the journey, out of the city of Stonemount and back to her childhood home after nearly thirty years.

Back to Millbury Peak.

She stumbled into a standing suitcase. The eyes of its owner tore at her flesh as she knocked it over and scrambled to regain her footing. She dared not look back as she struggled away, silently cursing the letter to have dragged her back to this unfamiliar hell, to have ripped her from her haven hundreds of miles away, forcing her to trade her cottage on that bleak, storm-soaked island for a town she hadn’t called home for decades. Not since the accident. Not since the seventeen-year-old had found in white corridors and hospital beds a new home. But this wasn’t about her. No, this was about an elderly lady, butchered. She was returning to Millbury Peak for her mother, her sweet, slaughtered mother. She slipped a hand into the leather satchel—

It would have held.

—and felt the coarse hemp of the noose against her fingers. She shouldn’t be here. She would have been gone—

It was strong, solid.

—had it not been for the detective’s letter. Gone to nowhere, forever. No more knives, no more eyes. She’d planned to be gone. She should have been gone.

The beam would have held. It was strong, solid. It would have held.

With desperation she glanced around, the exit to this damned train station still hidden from view. She spotted a gap in the bodies. Through this gap she spied solitude: the open door of a bookshop, deserted. She went to it.

The woman lunged through the door, the teenage cashier behind the counter glancing up momentarily before returning to her magazine, uninterested. She shuffled between the rows of bookcases and backed into an obscured, shadowy corner to calm herself. She passed her hands over her bunned hair, quickly checking the headful of clips and clasps before once again reaching into the satchel. She closed her eyes as she ran her fingers over the coiled noose. The knives, the eyes, the faces. Soon, they’d all be gone.

Soon, she’d be gone.

She was turning to leave the bookshop when a thought came to her. A gift for her father, how nice.

just bruises

After all, they were separated by decades from their last meeting. Yes, she’d see if she could pick up one of her novels for him. How lovely, how nice.

My love, they’re just bruises. He would never hurt us, not really.

She was tiptoeing through the bookcases searching for the romance section when, upon turning a corner, she found herself in the midst of a towering dark figure. She reeled back, before realising the figure was a cardboard cut-out. The blood-red shelving of its book display fanned around the figure, macabre imagery making it obvious as to which genre it subscribed. The man depicted in the life-size cut-out wore a dark turtleneck and tweed blazer, an expression of calculated theatricality staring through thick horn-rimmed glasses. The sign above read:

Horror has a name:

Quentin C. Rye

Choose your nightmare – if you dare

The display’s centrepiece was a pseudo-altar upon which sat the author’s latest release, a hardback titled Midnight Oil. She was turning from the display when her eye caught a thin volume squeezed between spines of increasingly doom-laden type, many screaming the words NOW A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE. The novel calling to her had only two words trailing its spine, two words that seemed to speak to a place buried deep within her. She reached for the book.

Its cover depicted a woman standing in the middle of a road, an emerald green dress flowing behind her in the fog. This road was empty but for one vehicle: a rust-coated pickup truck from which flames billowed, flying in its wake like tin cans from a wedding car. It tore towards the mysterious woman, who stood fearless in the face of the hurling metal. Horror Highway, the title read.

Suddenly, blinding pain.

The paperback dropped from her hands. Agony flashed through her head, tearing like a claw, then fell away as quickly as it had risen. She looked down to find her knuckles white around a wheel that was not there. Struggling for breath, she released her imaginary grip as a stray strand of hair floated into her vision. In a panic, she picked a fresh kirby grip from the handful in her duffle pocket and fastened it amongst the mass already intricately fixed. A loose strand meant something out of place. Something out of place meant disorder. Disorder meant disaster. She closed her eyes and thought of those long white corridors, sterile and simple, everything in its place. Her breathing settled. She’d never really left hospital, or maybe hospital had never left her. She slowly opened her eyes and turned from the Quentin C. Rye display. Find the book – it’ll be nice – then get out of here.

…he would never hurt us.

Romance read faded lettering above a shelving unit at the far end. She stepped towards the unassuming section and traced a finger along the alphabetised volumes towards W.

The cashier scanned the book’s barcode, offering the woman not a glimmer of recognition.

Just how she liked it.

***

‘From one writer to another, being spotted with your own book ain’t the most flattering of images.’

The voice materialised from many. She stood at the pick-up spot on the street outside the station, hesitating before looking around to the source of the voice. She glanced instead at the book in her hands as if to remind herself of whom the voice spoke:

A Love Encased

The latest in the Adelaide Addington series

Renata Wakefield

‘Miss Wakefield,’ the voice said with a New England twang, ‘it’s a pleasure. Big fan.’

She turned to find a pair of thick horn-rimmed glasses watching her, the same glasses from the Quentin C. Rye display. The same face from the Quentin C. Rye display.

Quentin C. Rye.

‘My wife is anyway – ex-wife, that is.’

Her mouth refused to open. The burning pickup truck and emerald green dress filled her head.

‘Didn’t mean to startle you, Renata,’ he said, slipping a fat leather notebook back into his blazer. He ran his fingers through slicked back hair shot with streaks of grey, then held out a hand. ‘Don’t mind if I call you Renata?’

So many years avoiding human interaction and it should be this American to greet her upon resurfacing? Of all people, of all eyes, why were his welcoming her back to the place she hadn’t called home for three decades? You couldn’t write it. She should know.

Renata stared at the outstretched hand.

‘Your work’s kinda outside my field of expertise,’ he continued, twirling a pen between the fingers of his other hand, ‘but I’ve been assured you’re quite the talent.’

‘I’m sorry, I—’

‘Name’s Quentin. The local cops asked me to help with the investigation after your Mom’s…uh…’ His brown frames glanced over her shoulder. ‘Detective! How’s it going? You guys know each other, right?’

The bulky detective stepped towards Renata, his wrinkles multiplying as he strained against the afternoon sun. ‘We did a long time ago.’ He smoothed his long navy raincoat, chewing on a toothpick straight from a forties noir. ‘Maybe long enough for you to have forgotten. It’s Hector, Detective Hector O’Connell.’ He held out a hand. This one she shook, noticing its slight tremble. She risked a glance at the man. He was right: she barely remembered this greying face in front of her, but she did recognise something pained in that deep-set gaze. Not the beginnings of jaundice-yellowing looking back at her, but something else, something that stared from every mirror she’d ever gazed into. Whatever it was, it didn’t stab with the same ferocity as those in the station.

She looked away.

‘Your parents have been friends of mine since you were a girl, Miss Wakefield,’ he rumbled, scratching his sweat-stricken bald head. ‘I’m the officer who contacted you following your mother’s death.’ Then, lowering his voice, ‘This must be a lot to take in. There’ll be time to talk in the car, but know that Sylvia Wakefield was loved by everyone in Millbury Peak. We’ll find her killer.’

Millbury Peak: a name both vague and clear as crystal.

‘I’ll follow,’ said Quentin. A cigarette had replaced the pen twirling between his fingers. ‘Listen, I’ve rented a little place on the same side of town as your dad’s house—’ Little place. The bestselling horror novelist of all-time had rented a little place. Renata glanced at the detective, sensing from him the same cynicism. ‘—so I’ll be nearby if you need anything. Besides, I’ll see you at the funeral tomorrow.’ He pulled a crumpled packet from his blazer pocket. ‘Kola Kube, Ren?’

Ren…?

‘Mr Rye,’ Hector began, ‘I’d ask we reconvene after the service. Sensitivity is paramount at this time, and your presence at Sylvia’s funeral may be unwise.’

Quentin nodded, stuffing the packet back into his pocket.

The detective took Renata’s meagre suitcase and led her to a battered Vauxhall estate, as tired and worn as its owner. A carpet of empty whisky bottles, no effort having been made to hide them, clinked by her feet on the floor of the passenger side. His sweat-laden brow, trembling hands, and yellowing jaundice eyes suddenly made sense. She looked warily out at Hector.

‘Small suitcase, Miss Wakefield. Travelling light?’

‘I won’t be around long.’

The detective smiled and gently closed the passenger door as she stuffed the book bearing her name into her satchel. Rope brushed her finger.

It would have held. The beam, it would have held.

The slam of the driver’s door made her jump, causing further clinking at her feet. Hector glanced at the glass carpet. ‘You should know, I just quit,’ he said. ‘Still to clear those out.’ He pulled an old pocket watch from his tatty waistcoat – navy, like the raincoat, shirt, trousers, and every other article of clothing besides his shoes – and popped the cover’s broken release switch with his toothpick. ‘It made me slow, sloppy. The drink, I mean.’ He gazed at the timepiece. ‘Going to have to sharpen up if we want justice for your mother.’ He stared at the pocket watch a moment longer, then closed the cover and slipped it back into his waistcoat. There was a roar from behind. ‘These Hollywood bigshots,’ he grunted, pulling himself back to reality as he wrestled the car into first gear, ‘need to be seen and heard wherever they go.’ Quentin’s motorbike revved again. ‘Never thought I’d have a Harley tailing this rust bucket.’ The estate coughed to life and dragged itself from the car park.

The main road to Millbury Peak passed through twelve miles of lush English countryside beyond the city of Stonemount. Their route ran alongside the ambling River Crove, its waters losing interest intermittently to swerve off course before re-emerging from behind the oaks and sycamores. Renata gazed at the rolling fields. The air, smell, and purity of the green expanses reached to the girl she once was. Her reverie was shaken by the bellowing of Quentin’s bike from behind, begging for tarmac.

Hector yanked the gearstick, a cough hacking from his throat. ‘It’s been decades, I understand that. If I had my way you wouldn’t have been called back to Millbury Peak at all. Still, procedure’s procedure, as Mr Rye kept telling me.’

‘Why wouldn’t you want me called back?’ Renata tensed. Was she doing this right? She curled her fingers, pushing her long nails into the palms of her hands. ‘I’m sorry, it’s just…well, I’ve been away a long time, but she was still my mother.’ She hesitated. ‘And may I ask, Detective…why is a horror author assisting in a murder investigation?’

Hector jabbed his teeth with the toothpick. ‘I was thankful for us having this time together before the funeral tomorrow, Miss Wakefield. There’s things you need to hear.’ He wiped the pick on the torn polyester upholstery. ‘I’d like to be the one to explain the circumstances of your mother’s death. I’d rather you had a reliable account to weigh any rumours against. The manner in which your mother passed was somewhat…’

His bulk shifted.

‘…brutal.’

Now it was she who shifted. What ‘brutal’ end could Sylvia Wakefield possibly have met? Locking her eyes on the asphalt streaming beneath them, she cobbled together a mental image of her mother’s face. So many memories washed away piece by piece with every passing year, but Sylvia’s face remained, even after all these decades. Still, it had been so long. Why had she let the death of a virtual stranger postpone her suicide? How could her end to end all ends possibly get sidetracked by some woman she hadn’t even seen in—

Promise you’ll be there for him if anything happens to me.

She clenched her fists.

‘As for Mr Rye,’ Hector continued, ‘you have every right to ask why he’s here. The nature of the murder requires his presence, Miss Wakefield. You see, from the evidence available at this time, it seems the incident was…how can I put this?’ He paused. ‘Inspired by him.’

Renata looked up.

‘Not that he’s a suspect.’ He rolled his shoulders as if preparing to jump the tired Vauxhall over a ravine. ‘I’ll be straight with you. Sylvia – that is, Mrs Wakefield – was found in the church across the fields from their house, the same house you grew up in. You remember the church, yes? The one with the clock tower?’

Clock tower. Renata’s lips hinted a smile.

‘Miss Wakefield, we have reason to believe whoever’s responsible for your mother’s death was making a statement.’

She felt like a patient being drip fed. Suddenly she knew how the crawling Harley behind them felt. She took a deep breath. ‘Detective O’Connell, yes?’

‘That’s right, Miss Wakefield. Or Hector, whichever you’d prefer.’

She picked at her beige Aran knit. ‘Detective O’Connell, I’ve come a long way to say goodbye to my mother and to make sure my father’s in good hands.’ …my love, they’re just bruises… ‘If you don’t mind, I’d ask one more thing on top of the kindness you’ve already shown.’ A strand of wool came loose. ‘Be straight with me.’

For a fleeting moment she allowed his stained eyes to meet her own. She’d spent a lifetime filling pages with other people’s emotions, yet, living the life of a recluse, she had little personal experience of such things. Somehow, through second-hand knowledge gained in a childhood lost to books, her writings had become like the voice-over in a nature documentary, expert narration on something she could see but never touch. That same narrator gave a name to the thing behind this man’s eyes, muttering it in her ear: sadness.

‘Yes, I apologise,’ he said. She felt him flatten the throttle. ‘Your mother was found bound on the church altar. I’m afraid…well, I’m afraid she met her end by way of…’ He cleared his throat. ‘…fire.’

The estate lurched as if the man had just broken the news to himself.

‘What are you telling me? She was burned?’

‘Yes.’ The detective straightened. ‘The remains of Sylvia Wakefield indicate she was restrained and set alight. However, I must add there’s no evidence to suggest she was conscious throughout. No gag of any kind was recovered, implying there was no need to prevent unwanted attention by way of, well, screaming. For this reason I surmise she was rendered unconscious or passed away before her…’ He swallowed. ‘…lighting.’

Her stomach cartwheeled, then whispered: That’s your mother he’s talking about, the woman who raised you. Burnt. Like a witch.

‘A note was found near her body, Miss Wakefield. It’s this note that links the crime to Mr Rye. His most recent novel, a thriller by the name of Midnight Oil, features the strikingly similar scenario of a woman being bound and set alight upon an altar by the story’s antagonist, who recites a rhyme throughout the murder. Aside from the method of execution, it is this rhyme that connects your mother’s death to Mr Rye’s latest work.’

‘The note,’ she said, eyes cemented to the grey conveyor belt passing beneath, ‘my mother’s killer left the rhyme at the scene?’

‘Midnight, midnight…’

His voice lowered.

‘…it’s your turn. Clock strikes twelve…’

Her breath caught in her throat.

‘…burn…’

She felt her hands tighten around that imaginary wheel.

‘…burn…’

She thought of the flames.

‘…burn.’

White light exploded from infinite points. She gasped as the pain tore through her head.

‘Miss Wakefield, are you all right?’ Hector asked. ‘I said too much. You understand I just wanted you to hear the truth from a reliable source.’

The motorbike lost patience and powered past them. Renata ran her fingers over the coiled noose in her satchel, stroking the coarse hemp like a cat in her lap. Soon she’d be gone.

Her breathing levelled.

‘Sorry, no. I mean, it’s alright,’ she stammered. ‘I’m just tired from the journey.’ Her hand stilled on the rope. ‘Has Mr Rye been questioned?’

‘Yes,’ said Hector between chesty coughs. ‘He cooperated fully and his alibi checks out. Poor man. Years spent writing the damned thing and some psycho comes along only to use it as a how-to manual.’

Poor man, indeed. Forges a career in torture porn, makes millions of dollars, and finally inspires someone to set fire to an old lady.

‘Yes, pity,’ she agreed.

‘Anyway, he’s devastated at the thought of his work having played a part in all this. Personally, I can’t stand what he does, but I respect his efforts to put things right. He rented his…’ Hector smiled. ‘…little place, and has done everything he can to help with the investigation. He’s become quite the regular around Millbury Peak.’

‘And my father?’ Renata asked hesitantly, rubbing her wrist. ‘What’s he got to say about Mr Rye?’

The detective’s smile faded. ‘Still wears that same old vicar garb, but don’t be fooled: he hasn’t much positive to say about anything these days. That’s another reason I wanted to explain to you the circumstances of Sylvia’s – I’m sorry, Mrs Wakefield’s – death. It’s better coming from me than him, I think you’ll come to agree.’

She already did. Her entire adult life lay between this day and the last time she’d seen her father, and yet the spectre of Thomas Wakefield had always loomed, like the ghost of a man not yet dead. Through the vast void of time, his fist forever reached.

She squeezed the noose.

…he would never hurt us.

***

The afternoon sun slid down a cool autumn sky as the Crove, in all its fickle meanderings, finally reconvened with the lurching Vauxhall. Quentin’s Harley had long since shrank into the horizon, leaving behind only the coughs and splutters of Renata’s ride. She gradually began to notice the lush fields and clear sky lighten in tone.

They were driving into a haze of mist.

Detective O’Connell switched to full beams and squinted through the windscreen. ‘Not far now, Miss Wakefield,’ he said. ‘Just as well. Can’t see a bloody thing.’

Shapes formed in the fog. Tight-knit ensembles of cross-gabled cottages and Tudor ex-priories emerged around them, triggering neural pathways long since redundant in Renata. The town was a snapshot dragged into present day, some kind of Medieval-Victorian lovechild refusing to bow to the whims of natural progression. You could practically sense from the rough brickwork and uneven cobbled roads the stubbornness with which this town opposed modernisation of any kind. It was stuck in the past, and perfectly content. The familiar forms of Renata’s childhood, of this frozen town, assembled themselves as Millbury Peak unfolded in the mist.

Yet there were still gaps in her memory, scenes spliced beyond repair. There was just one thing of which she was sure: she shouldn’t be here. She’d come back on the strength of a promise made when she was just a damned child. What had she been thinking? By now, it should all have been over.

It would have held.

‘That’s Mr Rye’s rented house on the left.’ He pointed to the Georgian manor rolling past, Quentin’s Harley already leant against a side wall. ‘I can tell he meant what he said. He really does want to help if you need anything.’

‘I’m sure my father and I will be fine, Detective.’

Their route was leading out the east side of Millbury Peak when she spotted a stone finger pointing to the sky. Renata’s eyes widened. The clock tower dominated the fog-drenched fields.

Hector glanced over. ‘Must be a lot of memories.’

‘Yes,’ she replied.

And yet so few.

***

Detective O’Connell shut the engine off outside the house and heaved the handbrake with both hands. Renata pulled the book from her satchel.

‘A gift?’ asked Hector.

She looked at the thin paperback. ‘I thought my father might like to see one of my novels.’

She felt the detective’s gaze linger on the book in her hands. He scratched his stubble. ‘Like I said, your parents are old friends of mine. I watched your father’s health decline, his body wither, the untreated cataracts turn him blind. Thomas is not the man you knew. Although in many ways…’ He glanced at the house. ‘…he’s exactly the same.’

She stuffed the novel back into her bag and smiled at the dashboard. ‘Well, I suppose I can’t expect a blind man to get too excited over a book.’

‘I wouldn’t expect your father to get excited over anything, at least not in a good way.’

She stepped out of the passenger door onto the gravel track and stared at the towering monstrosity before her, part of her begging to get back in the car and escape to somewhere else – anywhere else. She tightened her coat.

It was a memory made real. The two-storey Victorian farmhouse had been acquired long ago by the parish for use as the town vicarage, lying conveniently close to both Millbury Peak and the church a few fields over. The struts of the wrap-around porch had seemed past their prime when Renata was a girl; now, the boards and beams resembled mildew-ridden sponges, with each of the roof’s wooden shingles seemingly ready to fall to the ground with a splat.

The entrance, bay windows, veranda: all irrationally tall. The entire house looked stretched like an absurdist caricature. It dominated the fields, both a monument and a tomb. Most of all, the thing was spooky, an image of cut-and-paste cliché from a Quentin C. Rye dust jacket. The Dreaded Ghost House of Doom. Or something.

Hector set down Renata’s suitcase and joined her in the shadow of the house. ‘I won’t get in the way of your reunion,’ he said. ‘I’ll be over to drive you to the funeral tomorrow.’

She stole a glance. Sadness, that expert narrator muttered again. She jerked her gaze back to the house.

‘I really am sorry,’ he said, voice low. ‘Sylvia was an admirable woman. Mr Rye does want to assist any way he can, and I’d like to extend the same offer.’

‘Thank you, Detective. I’ll remember that.’

‘You have a life outside of Millbury Peak, Miss Wakefield,’ he whispered. ‘No one will judge if you return home after the funeral.’

‘I have to ensure my father’s wellbeing,’ said Renata, rubbing her hands. They were clammy from the journey and could do with a good wash. ‘Once my brother and I have arranged care for him, I’ll be leaving.’

It’ll hold.

Hector’s eyes dropped. ‘Miss Wakefield, Noah won’t be coming.’

She straightened. ‘He won’t be attending the service?’

‘Actually, it’s unclear whether your brother will be coming to Millbury Peak at all.’

She bit her lip. ‘Why?’

‘It was another officer who spoke with him, so I didn’t get all the details. Family commitments or something.’

As excuses to dodge your own mother’s funeral went, ‘family commitments’ was pretty rich. Like everything else in this town, her memories of Noah were vague. There was enough, however, to render this behaviour all too believable.

‘I see,’ she said through clenched teeth. ‘Nevertheless, I’m glad you understand I may not be staying long.’

She felt him level his gaze.

‘Yes. You should leave.’

A sharp wind blew up her back. Before she could respond, the stocky detective was trudging back to his car, slamming the driver’s door, and turning on the ignition. He rolled down the window.

‘My regards to Mr Wakefield,’ he said. Then, in a hushed tone, ‘Remember, I’m here.’ The rusted estate lurched into the fog. She took a deep breath.

The woman looked up at the house.

2

The house looks down at the girl.

It’s like a scary face, maybe even scarier than Mr Farquharson’s when she hadn’t done her homework, or Mrs Crombie’s when she caught her snooping around her garden, or Father’s when he’s having an angry day. Come to think of it, maybe not scarier than Father’s. His could get SUPER scary.

But the house is like a scary face, that’s for sure. There’s loads of windows – not too many to count, but maybe too many to count on one hand. There’s two above the porch, glaring at the little girl like a pair of eyes. The front door is a mouth, ready to gobble her up.

Anyway, it’s definitely scary, and not the kind of surprise she was hoping for when Mother said Father was waiting in the car to take them somewhere. No ice cream, no penny chews, no trip to the funfair. They have popcorn at the funfair, that’s what she’s heard. Not that she knows much of that kind of thing, but the funfair would definitely be better than this big weird house. Besides, she might only be five-and-a-half, but she still hasn’t missed the fact everything’s been packed into cardboard boxes the past few weeks. She has a pretty good idea what’s happening, has done for a while. She just wishes they’d spill the beans instead of treating her like…well, a five-and-a-half-year-old.

SURPRISE!

Nope, that’s not what Father had said, maybe like you’d say to a five-and-a-half-year-old when you’re about to take her to the circus or the beach or the funfair with the popcorn. Instead he’d just made that gruff snorting noise that always made her nervous but also snigger a little inside ‘cause that’s the noise donkeys make ‘cause she’d seen one in a field near school once and she even thought Father looked a bit like a big stern donkey sometimes but she wouldn’t say that to his face ‘cause she knew what happened when you said much of anything to his face ‘cause Mother sometimes did and one time the little girl had been hit by the netball at school and it really hurt and that’s probably what Father did to make the bruises appear on Mother’s face – a big fat netball right on the nose. Bop.

‘What do you think, love?’ asks Mother with that wide encouraging smile of hers. The girl marvels at the woman’s perfectly arranged hair. How does she get it so perfect? Mother squeezes her hand. The girl loves it when she squeezes her hand. ‘What a big house! Think of all the places to play!’

There’s a duck pond at the other house, the house called home, and she’s wondering if it’s coming with them. She’s too scared to ask so she just pops a big smile on her face and peers around, trying to find a good pond-spot for when it gets unpacked. She says a quick little prayer in her head, asking Jesus to make sure the pond is brought along.

Father seems more interested in the big glass crucifix that usually sits on the table where other kids might have a TV but where Father has a big glass crucifix. The boxes were thrown in the back of the car like Mr Chisolm throws the squishy mats back into storage after gym class, but that big glass crucifix, oh, it sat in Father’s lap the whole way here. That’s what he seemed to care about most on the drive. That, and the big creepy painting of the water and the sad faces. She was pretty disappointed to see that hadn’t been forgotten. If he was going to leave anything, it should’ve been that. Or the stupid bookcase he’d had moved in before they even got to see the place.

‘Looks lovely, Mother!’

Father sets down the big glass crucifix and fiddles with the front door, his hands twitching and quivering – always twitching and quivering. Soon, the house’s mouth is all wide open like a big old train tunnel. Steam trains go straight into those tunnels, they don’t even slow down! The girl always found that funny ‘cause she slows down whenever she goes through a door ‘cause of that time she went through one too fast and BAM, there was Mother crying and Father yelling and who wants to see that? Then again, steam trains probably don’t have mothers and fathers, so they don’t care.

Father’s red hair is all shiny in the sun. He stands next to the big old open mouth with the big glass crucifix next to him on the ground. He’s looking down at her, tapping a single finger against the side of his thigh, and he wants her to go in and the little girl wishes she had a steam train ‘cause right now she’s not feeling too cheery about walking into that big old mouth.

Trains are brave. Maybe she’ll be brave.

Maybe she’ll be a train.

So Mother squeezes the little steam train’s hand and off she goes, full steam ahead, ‘cause that’s the only direction big brave trains go.

Choo-choo!

Soon the little engine is puff-puff-puffing ahead and nope, Mother’s not even holding her hand any more ‘cause she’s chug-chug-chugging all on her own, heading straight for that big tunnel. Trains are brave. Trains aren’t afraid of some stupid old house.

The little train tears up the porch’s three steps ‘cause that’s what trains do. Well, they don’t really go up steps, but this is a special train. Three steps is nothing!

Except there’s a fourth.

The little engine clips her wheel and tumbles to the ground. She bashed her whistle on the step but that’s okay ‘cause the whole thing’s sort of funny anyway.

Oh, and she fell into the crucifix. It’s in a zillion pieces now.

That’s not so funny.

The gruff old donkey starts huffing and puffing and his jaw is sticking out further and further and his hands are quivering more and more and his face is turning red as a balloon and he scoops the trembling little train under one arm and off they go into that big old mouth and Mother’s shouting but Father slams the house’s mouth shut and it’s locked now so Mother stays outside and the little steam train’s on the floor and Father’s staring down at her and she doesn’t feel much like a brave little train no more. There he is, see? Standing over her, fists clenched.

‘New house, new rules,’ he says.

Gruff-gruff goes the donkey.

‘By the Holy Book, by the sacred plight of our Lord and Saviour, that woman shall give me a son. And YOU shall bring upon yourself the solemnity of the meek.’

Bang-bang goes the door.

‘Do you have any idea how long it took her to give me YOU?’

Waah-waah goes Mother.

‘Lower thy head.’ He presses her face into the rough wooden floorboards. ‘Lower thy spirit before God, child, and offer upon Him a change in will, a strengthening of service.’

Flutter-flutter goes a little moth, landing next to her face.

‘Change in will, strength of service. SAY IT.’

No more coal for this little engine.

‘Chay-chay-change in…Father, please! You’re hurting—’

‘CHANGE IN WILL, STRENGTH OF SERVICE.’

‘Change in…in will…’

‘STRENGTH. OF. SERVICE.’

‘Streh-streh…’ The girl chokes on the floorboards. ‘…strength of service.’

‘Yes.’ Her father lowers his face to hers, his red hair not so shiny out of the sun. ‘Humble thyself before His will, girl. This house shall be our salvation. Here, our family will grow. Once she finally fulfils her function, once she gives me my son, he shall grow into a man under this blessed roof.’

His eyes cut into her.

‘And YOU, my child…’

Like knives.

‘…shall learn your place amongst the meek.’

Why are they like knives?!

‘Now, get up. But forever keep your head to the ground. Find your place amongst the meek, girl, where you belong.’ He raises a twitching, quivering hand, its fingers slowly clenching.

‘Tell me you see, Renata.’

Choo-choo goes the fist.

3

There was a constant in Millbury Peak: pure, wholesome tradition, running through the town’s history and into its present like an arrow. Change was not on the menu. The small but fervent council had devoted three years to challenging and eventually overruling the proposed development of an industrial estate on its south-east corner, an orgy of concrete that was the complete antithesis to this thread of tradition so vehemently held by its residents. The rabid little consortium never once backed down, tirelessly standing guard over the town like a pride over its cubs.

Traditional values kept Millbury Peak on the straight and narrow as generations of townsfolk dogmatically followed in the footsteps of their forefathers, at times fanatically defensive over their treasured sense of unity. Don’t come a-knockin’ with anything on your mind other than the local crochet club or the biannual gardening gala and you’ll get on just fine.

And today, as autumn sank and winter rose, something neither regular nor rare for the East Midlands maintained a stubborn watch over the town and its surrounding grassy planes: the mist remained.

The small congregation huddled tight as crowds of headstones kept a solemn watch through low-hanging fog. The group would have liked to be larger, but Thomas Wakefield, his unseeing eyes gazing aimlessly into the mist from his rusty wheelchair by Renata’s side, insisted on a modest gathering. He also demanded the service be held in the cemetery surrounding the decrepit, now abandoned church in which he’d spent his life giving impassioned sermons before retirement. This was all in spite of the still pimple-faced Edwin Ramsay’s – Thomas’s successor as town vicar – protestations, for whom the newly built replacement in the heart of town was Millbury Peak’s ticket to modernisation. A wish shared by no one.

The eager young cleric had taken over as vicar after Mr Wakefield’s declining health tore him from his charge. The new church, which replaced the crumbling relic overlooking today’s humble burial, was Ramsay’s brainchild; five minutes with the rosy-cheeked clergyman was enough to witness his pride in the pale, plasterboard facility bubble over like champagne. Thomas Wakefield’s glass, however, was very much empty. His decision regarding the ceremony’s venue had been final. He insisted on a great many things on a great many days, usually from his loyal wife, Sylvia – until she’d been burnt alive upon an altar barely thirty yards away.

Every breath Renata drew was a terror, with so much as a twitch of her finger feeling like an announcement of her presence. She kept her gaze fixed on the rippling grass, away from the eyes – those carving knife-eyes – eyes that speculated, judged, concluded.

Where’s she been all these years?

Is she even bothered?

She could at least shed a tear.

Not for the first time during the service, she risked a glance above to make sure the clock tower remained. Sure enough, her childhood friend was still there, looming over the crowd. It hadn’t abandoned her, not like the others.

The vicar’s monotonous drawl droned on while the police tape over the church’s sealed entrance fluttered noisily in the wind, a hyena cackling from the sidelines.

‘As in life, so in death, Sylvia Wakefield shall inspire us to live our lives fully and with courage…’

The coffin sunk with a terrible creak.

‘…and upon those who adored her most, let God grant solace in His promise of reunion. For in all the Wakefield family have endured, all they have lost—’

Thomas snorted, his blind eyes locking on Ramsay.

‘—uh, their place in Heaven is ensured. I ask the friends and family of this cherished woman to bow their heads for Sylvia Wakefield’s favourite prayer.’

There was a bellowing roar.

The Harley skidded to a halt on the track, spraying dirt into the face of a stone cherub. Despite Thomas’s drowning in the fraying, black robes of his old cassock, Renata was still able to detect the tightening of his emaciated frame. His face glowed red.

Like a balloon.

‘What is that accursed racket?’ he spat.

Quentin stepped off the bike and approached the congregation amid tutting and shaking heads. He knelt in front of the elderly man. ‘Mr Wakefield,’ he announced with clichéd US theatricality, ‘sorry for interrupting. I’m here to pay my respects to what I’m told was an awe-inspiring woman, an angel who—’

‘Get this beast OUT OF HERE,’ roared Thomas. Spit dotted Quentin’s glasses.

The young vicar lowered his prayer book. ‘Mr Wakefield,’ he said, ‘Mr Rye consulted with me before the funeral and I gave him my blessing. He feels profound remorse for his novel playing any part in Sylvia’s death, and has expressed a deep desire to—’

‘The man’s a damned hatemonger, Ramsay!’ Trembling fingers tugged at his yellowed clerical collar as he spoke. ‘With God as my witness I want this foul soul away from my wife.’

Quentin rose, wiping his glasses. ‘Mr Wakefield’s wish is my command,’ he said, smiling at the shocked faces. ‘I’ll leave you folks to it. But know this.’ He scooped a handful of dirt and held it over the open grave. ‘I’m gonna do everything I can. Sure, I don’t know who did this, and I can’t give Thomas and Renata back their beloved Sylvia…’ The dirt trickled from his fingers. ‘…but that doesn’t mean I can’t help make things right.’

He looked to his audience, shaking the remaining dirt from his hand.

‘I’m keeping on my rented accommodation in Millbury Peak. My production company’s gonna film the latest movie adaptation of my work right here in your magnificent town.’

Jaws dropped.

‘We’re talking big-budget here, guys. Trade, jobs, recognition. It’ll bring all these things to Millbury Peak. Nothing can replace Sylvia,’ he looked at Renata, ‘but that won’t stop me giving something back.’

‘Out…NOW,’ exploded Thomas, before breaking into a coughing fit. Chatter erupted.

‘He can’t do this—’

‘Nobody wants him here—’

‘Mr Wakefield’s wife just died—’

Renata, paralysed with terror, watched Quentin walk silently to his bike. The prattle was suddenly decimated by another roar, this time from the tower as its bell tolled noon. She turned her eyes to the great clock face of the stately stone column, then, glancing back down, met Quentin’s eyes as he revved the engine. He flashed a gentle smile before tearing down the track back towards Millbury Peak.

***

‘Father,’ she’d said, ‘it’s been a long time.’

Their reunion had been blunt. She’d found Thomas alone in front of the dead fireplace, save for the decrepit grey mongrel in an immobile heap by his side. The rusted tag hanging from its collar read the name ‘Samson’, the same name transferred to every grey mongrel Thomas had owned through the years. She wondered what number he must have been on now. Samson Mark VI? Grey mongrel replaced by grey mongrel. If only everything in life was as simple as Samson.

Ramsay had been taking care for the former vicar prior to Renata’s arrival, before terminating his duty and leaving the responsibility of her welcome home party to the old man and his senile canine companion. She’d froze before approaching the gaunt figure in the wheelchair, horrified at the pastiche of memories that was her childhood home – or, more specifically, horrified at what now encased the home.

The minimal décor still functioned only in painting a picture of a home, not creating one. In this respect, little had been removed or added since she last stood in these wide open rooms, with mainstays such as the heavy doors and thick oak shutters having proved immutable through the passing decades, not to mention the grandfather clock by the door, its hands now dead, the eternal ticking of its pendulum silenced. The main divergence from memory, and the source of Renata’s horror, was the house’s state of uncleanliness. Corners where Sylvia’s duster once obsessively frequented were now pinned with festering cobwebs, while dust floated from the Persian rug as Renata crossed the hall. The door handles even left a sticky residue on her fingers, a thin scum presumably covering much of the house. She’d frantically wiped her hand on her long pleated skirt.

So much out of place.

The week since her mother’s passing wouldn’t have been sufficient for this degree of filth to take hold; Sylvia Wakefield had quit her compulsive cleaning long ago. Aside from her mother’s obvious abandonment of a once manic cleaning habit, the damp-plagued ceiling and mildew-stained walls betrayed the presence of issues beyond the neglect of routine housekeeping duties. The house was a shadow of its former self.

Two whitened orbs had shot at her, glaring blankly, then resumed their vacant lazing in their eye sockets as she’d approached the armchair. The blindness of his eyes should have been a relief, but Thomas Wakefield didn’t need sight to put her on edge.

‘It’s good to see you,’ she’d said, dropping A Love Encased into a brimming wastepaper basket. Her pale face tightened in disgust as a cockroach scuttled over the binned book. She’d closed her eyes and thought of those white walls. So clean, so orderly. Everything in place.

‘I was sorry to hear what happened,’ she’d continued, eyes still shut. ‘Mother’s at peace now.’ Peering through half-closed eyelids, she’d seen the man’s face twitch, more as if recalling a forgotten detail than his deceased wife. ‘I’m going to care for you, Father,’ she’d continued, ‘until we can arrange something more permanent.’

Was now the time to ask about her brother, Noah? Her father’s leathery lips pursed. As part of a lifelong habit, one of his ragged fingernails tapped and scraped out some frantic pattern on the arm of his chair like a confusion of meaningless Morse code.

The lips tightened. The finger sped up.

Perhaps later.

She’d finally managed to coax something from the old man when enquiring as to the following day’s funeral arrangements – who would speak, was he acquainted with the minister, why hold it a stone’s throw from where his wife’s flesh melted from her bones just a week prior (well, maybe not that part) – to which he’d grunted some names and times and Bible verse numbers. His biblical utterances made her shudder. Bible studies had ended for Renata long ago, Baby Jesus having checked out of her life the same time as everyone else. That didn’t stop his mention jolting her like a defibrillator.

Suddenly she’d noticed the ghostly condensation following her father’s words. Her disgust at the state of the place had seemingly overwritten her sense of temperature. She’d knelt by the hearth, Samson watching through one half-open eye, and started a fresh fire. Flames lit the musty room, giving the man’s cracked face a warm glow. It was then the reality of whom she was knelt before dawned upon her.

Despite the atrophied muscles of his trembling, cadaverous form, the core of Thomas Wakefield remained, the part which caused grown men to hold their tongues and divert their gaze. The underbite protruded even further in his old age, seemingly reaching up for those wild, arched eyebrows – eyebrows of the same faded copper as the thin smattering of hair on his scabby head. His face looked like it had been smashed then glued back together, a roadmap of wrinkles consuming every inch of skin. As for his once-broad shoulders, they’d shrivelled to resemble a scrawny clothes hanger upon which sat his quivering head in place of a hook. The tattered clerical collar hung loose around his throat, beneath which threadbare robes sagged over a wasted body. Youth had abandoned Thomas totally. Although his shell was in tatters, the same man from her childhood lurked inside, fingers forever locked in that twitching fist. Her mother had made her promise to take care of this man should anything ever happen to her, but all Renata saw in that reeking armchair was a monster.

And tonight, the crispy remains of Sylvia Wakefield cast to the earth, here they were, father and daughter. With the carrots cut and potatoes peeled, Renata stood simmering water over the hot stove, staring into a bubbling oblivion. She stepped to the sink and turned the tap. Rubbing her hands under steaming water, she thought of the coffin, pressed down this very moment by six feet of soil. That sweet six feet should have been hers, it was meant to be hers, yet somehow her mother had taken her place, and she’d taken her mother’s place: by the stove, cooking for a monster.

It would have held.

Stonemount Central crept back into her mind. The thought of those eyes – those watching, scrutinising eyes – caused her heartbeat to quicken, her mouth to dry. She forced her thoughts back to those long, white corridors. Those sweet, serene corridors…

She calmed.

It hadn’t always been this way. Once, she’d been indifferent to the presence of others. She’d lived happily outside the waters of her mind, introversion a concept of no consequence. Everything had changed when her father moved them to the new house. The first time he’d raised his fist to the girl marked her permanent relocation to these waters, the never-ending narrative of her thoughts becoming her only place of peace.

Time marched on and reality transposed from the outside in. Thoughts and dreams and stories became the only plane in which she felt sane, her head breaking the water’s surface only when unavoidable.

Will you please pay attention in class?

The waters would part.

What did you learn in school today, girl?

She’d peer out.

My love, they’re just bruises. He would never hurt us, not really.

Back under she’d go.

It was this introversion she had to thank for her profession; her life as a novelist was down entirely to the waters of her mind, her font of fiction. This career in romantic literature was, in turn, to thank for her life of reclusion. It was also responsible for her sole experience of that thing called love – not that that had ever shown itself outside the pages of her paperbacks.

By the time they’d told her she was finally well enough to conclude her years in hospital following the crash, it had been obvious to all she was destined to live apart from the world, away from the pain that plagued her when around other human beings. Five of her novels had been published before even leaving care, and these provided her with sizeable unspent savings. Options, her doctors had called them. The option she’d suggested had been received surprisingly well, so long as she found her way back for regular checkups when instructed. What she’d proposed may even be for the best, they’d said. They were right. It had been for the best.

A two-hundred-year-old cottage on a secluded, unpopulated island in the Outer Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland – unnamed, save for the unofficial title afforded by neighbouring islands: Neo-Thorrach. Gaelic for ‘infertile’, the nickname originally referred the island’s inability to grow anything of any value to anyone, leading to its lack of habitation. Once word got around of the strange hermit lady in residence upon Neo-Thorrach, the name took on a dual meaning as the bored children of the islands concocted stories of the woman. The ‘Neo-Thorrach Buidseach’, she came to be called. The ‘Infertile Witch’. She was no witch, though. Far less glamorous. The sole inhabitant of Neo-Thorrach was nothing more than a second-rate romance writer who needed to be alone with her thoughts and live out her days at her Adler typewriter. Away from the eyes.

Now, in the presence of just two blind eyes, Renata and her father dined in silence. She ate little, her decade and a half of hospital food having permanently crippled her appetite in the years since. Her courage to mention Noah remained as absent as her hunger.

Thomas’s shaking grew worse as the evening wore on. She sat watching his trembling frame, curling her fingers into a fist to stab uncut nails into the palms of her hands. She looked at his twisting, yellowed talons. Maybe they weren’t so different, after all. Had she intended to give herself a few more decades, could this have been a window into the future she’d planned to abandon? It didn’t matter. Soon, nothing would matter. Disease and degeneration had picked away at her father through the years like a fussy eater, but something with a far greater appetite had torn into Renata. Thomas’s flesh was on a steady decline, but Renata’s once creative mind was ravaged; somewhere along the line, her gift for writing had flown from the tiny island of Neo-Thorrach, never to be seen again. For days at a time she’d sat at that typewriter, the rain and gales battering the stone walls of her cottage as doggedly as her publisher’s written demands for more cheap romance.

There was no escaping it. Inspiration had abandoned her.

As her ability to write had dissolved, so had her bank balance. Inhabiting an uninhabitable island was an expensive deal. Generator and purifier repairs were costly, not to mention food and fuel deliveries, forever left in an agreed location away from the cottage so as to maintain her reclusion. A private courier had even been required so as to be able to correspond with her agent and publisher. Manuscripts out, cheques in. That had been the arrangement, until the manuscripts stopped sprouting from her aged Adler. Then the cheques were replaced with demands for contract fulfilment. A couple of failed novels and the correspondence finally ended following one final ‘don’t write us, we’ll write you’.

And that was that. The writing ended and the debts began. She’d tied that noose as an alternative to being forced into bankruptcy, into offices and appointments, into repayment plans and probably a job in the real world. But the noose was put on hold following the detective’s letter. She’d have skipped the funeral had it not been for the promise. Her mother had gone through years of hell for her, and the responsibility of honouring the dead woman had possessed her like a demon. But where had that damned promise landed her? Back in this house after nearly thirty years with one of the parents who’d left her to rot in that hospital. She shouldn’t be here. She ran a finger over the outline of the rope crammed into the front pocket of her mother’s apron.

It’ll hold.

She knelt by the hearth, considering whether to restart the fire as Thomas’s unseeing eyes bored into the back of her head from his armchair. She turned and flicked a dirty-grey moth from a cushion before perching on the sofa. The moths had been a staple of the house for as long as she could remember, an enduring torment for Sylvia whose relentless cleaning had done nothing to dissuade their stubborn residency. Their place of nesting had always remained an enduring mystery, the pursuit of which her father strictly forbade.

She cast her eyes to the sprawling oil painting above the mantelpiece. The imposing spectacle had been a childhood horror; waves clawed at screaming men and women as they fought for higher ground, their expressions of dread detailed to perfection. As a girl, Thomas had ensured her complete understanding of the scene’s depiction: the Great Flood, rising to rip the accursed mortal coils from these vile sinners.

Her father was infatuated with the thing. He reserved a special look of adoration for the painting, one which only his beloved Noah, and maybe the latest Samson, ever found themselves on the receiving end. However, behind that wooden, fixed smile, Renata’s mother had held a very different sentiment for the framed flood, a sentiment which idled just outside the facility of Renata’s recollection.

Her thoughts were interrupted by Thomas’s spluttering. They’d sat in silence for hours, the fire now reduced to glimmering embers. She instinctively glanced at the grandfather clock, only to find its hands frozen in the same place as when she’d arrived.

‘It’s late,’ she said, working an antiseptic wipe over her hands. ‘Sorry, Father. I don’t know where the time went. I’ll get your medication.’

Renata made for the hallway and ascended the creaking wooden staircase, cringing as the hem of her ankle-length skirt hung dangerously close to the grimy steps. She glanced down the gloomy hall to Noah’s room at the far end, then squeezed into the small lavatory on the landing. She took the opportunity to give her hands a quick wash and adjust her hair grips, then opened the medicine cabinet. A pharmacy’s worth of bottles and blister packs awaited her, many of which bore the same name: Dexlatine. The muscle relaxant, as a note left by Ramsay had explained, was less a sedative and more a paralysis potion, a single pill having the ability to calm Thomas’s shaking body and, once the drug had time to take effect, subtly freeze his muscles into a motionless state. A tub of Vicks, bottles of painkillers, and packets of sleeping pills filled the remainder of the shelves, the latter of which would ease the mind inhabiting the paralysed nerves into unconsciousness. The medications were a drastic measure, but his temper was savage enough at the best of times. No one wanted to see how much worse it could get when sleep deprived.

Renata hurried back to the living room with Thomas’s dose of Dexlatine. She hoped it would ease the journey to the master bedroom, but she was slight of frame and the steep stairs proved a struggle. It was like carrying a downed climber the wrong direction to safety; how her mother accomplished the feat she’d never know. Stored on the landing was a second wheelchair in which she wheeled him to the bathroom. She had no trouble translating the scorching scowl he gave her at the offer of assistance.

The transfer of Thomas into his nightclothes was an awkward affair, during which he kept his cloudy eyes locked straight ahead on the discoloured wallpaper behind Renata. She pulled the sheets over him, wincing at the feel of the filthy fabric, and sat on the end of the bed, watching the quivering covers settle.

She placed a sleeping pill in his mouth and held a glass of water to his coarse lips. He swallowed then let out a long, rasping sigh. She looked down at the blister pack and bottle of pills in her hands. Her mind wandered back to hospital, back to that pure, perfect white. How she missed those corridors, those empty, endless—

‘What is it?’ he croaked suddenly.

Renata looked at him. ‘Father?’

‘Tell me what it is you want to say, girl. You’ve been stuttering like a freak all evening.’ Saliva hung from his lips like liquid stalactites. ‘Out with it.’

She glimpsed the man she used to know, still manning the cockpit of this ruined vessel. ‘I…well, Father, I…’

‘Lord, have mercy,’ he said. ‘The girl babbles like her mother.’ Renata jolted as dynamite suddenly exploded from the frail old man’s mouth. ‘SPEAK.’

She took a deep breath and threw a fresh shovel-load into the little engine’s furnace.

Choo-choo.

‘Father,’ she began, fingering her jersey, ‘sorry, but…I was hoping to ask you about, well…’ Another shovel-load. ‘…about Noah.’

In a Quentin C. Rye scary story, such a scene may have been embellished with the pattering of rain against the window, maybe some thunder and lightning for good measure, or the shadows of branches reaching across the room like bony claws. In this scary story, however, the evening was calm and fresh, the room well-lit and claw-free, yet the moment froze as if on a triple dose of Dexlatine. Within this paralysed second, she waited.

‘I expect you’d like to know when he’ll be joining us. I expect you’d like to know when he’ll be arriving…’

‘Well, I mean—’

‘…so YOU can leave.’

‘I’m sorry, Father. I just—’

‘Let me tell you what I’d like to know, girl.’ He struggled to his elbows, fighting the paralysis already taking hold. ‘I’d like to know why God gave me a girl, one who soiled my family with nothing but anguish and misery.’

She stepped back as the monster emerged.

‘I’d like to know,’ he snarled, ‘why after all these years of service, our heavenly Father took from me the only righteous thing in my life.’ His crooked fingers tried to reach for her but were held back by the medication, an invisible protector. ‘Except I already know the answers, child. I know because the Almighty has granted them upon me through the unfolding of tragedy – the tragedy of my family.’

Renata stumbled into the half-open door.

‘He has revealed to me that this family…’ His milky eyes swelled towards her, a torment on her flesh. ‘…is forsaken.’

Outside, the fields swayed gently in the placid breeze. Although it would return, the mist eased its watch for the night, the clear, crisp moonlight blanketing the calm comings and goings of the meadows surrounding the house. The clock tower was audible from across the pastures, tolling the midnight hour.

Renata’s hand gripped the doorframe. She watched in terror as the skeletal shape of Thomas Wakefield gave off a violent spasm, before finally sinking into the mattress. He stretched his face in her direction as he deflated, his jaw extending with unnatural elasticity.

‘Change in will…’ he hissed.

Tears stung.‘…strength of service.’

Get the rest of the story on Horror Hub here

Tritone’s love of horror and mystery began at a young age. Growing up in the 80’s he got to see some of the greatest horror movies play out in the best of venues, the drive-in theater. That’s when his obsession with the genre really began—but it wasn’t just the movies, it was the games, the books, the comics, and the lore behind it all that really ignited his obsession. Tritone is a published author and continues to write and write about horror whenever possible.