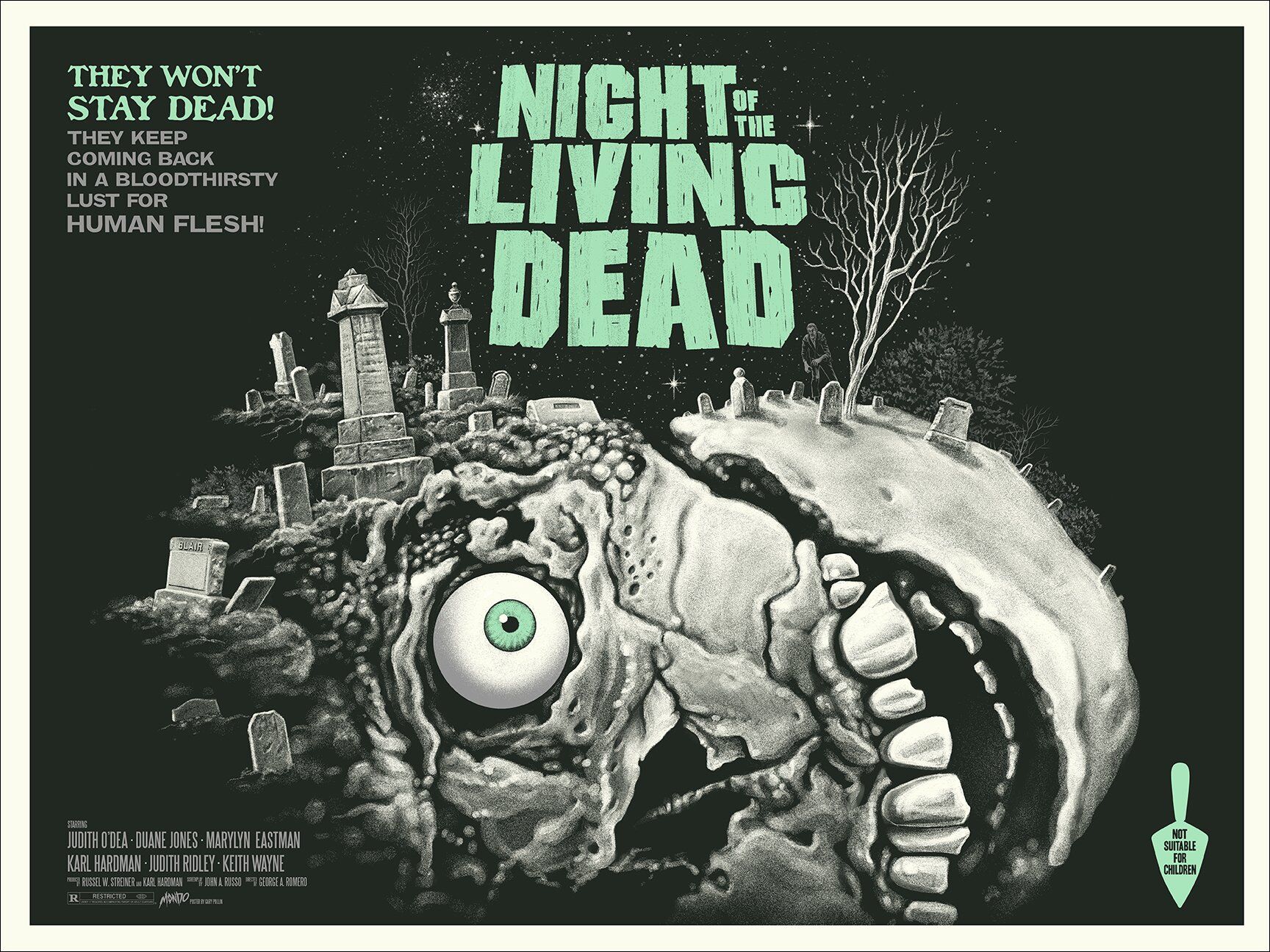

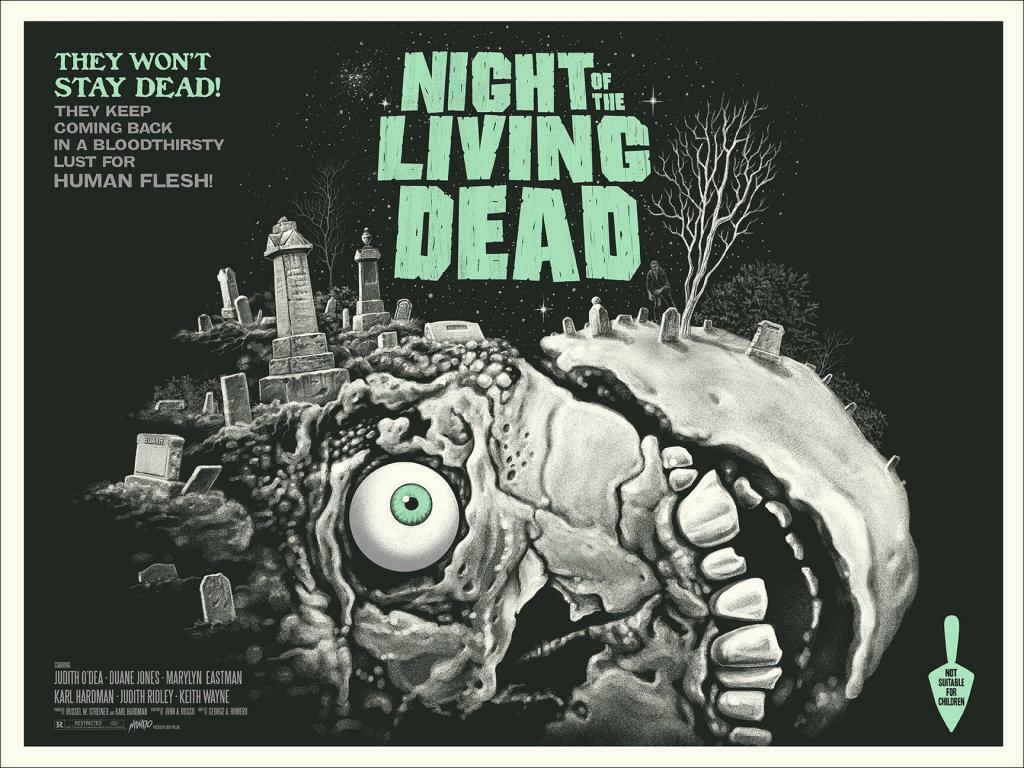

Night of the Living Dead (1968) was hardly the first zombie film—in fact, it was the fortieth, for those of you who like useless trivia facts—but it is possibly the most memorable of the older zombie classics. It’s not hard to see why it has persisted for the last fifty-three years, enduring beyond the renown of such modern zombie sensations, such as The Walking Dead (2010 – Present) and Train to Busan/Busanhaeng (2016). What most modern films and television shows of the horror genre seem to gloss over is their captive audience. Therein lies the opportunity for commentary on the civil rights issues that are still incredibly relevant in the present day.

One notable exception to missed opportunities for commentary being Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017)—but we can get to that one later. For now, we’ll just focus on the message of Night of the Living Dead. As Tom Gunning explained in his essay, “confrontation rules the cinema of attractions in both the form of its films and their mode of exhibition. The directness of this act of display allows an emphasis on the thrill itself—the immediate reaction of the viewer,” (“An Aesthetic of Astonishment”, 122)—this thrill that we get from controversial messages and images on display within films is one of the main reasons we watch horror. Excitement is king.

They’re coming to get you, Barbara!

Johnny in Night of the Living Dead (1968)

What is Night of the Living Dead about?

At face value, this movie is just a story about survivors of a zombie apocalypse stumbling upon one another, clashing personalities, and finally a begrudging combining of forces to fend off the zombie hoard that surrounds the farmhouse that they each found and decided to hunker down in for safety. One by one, these survivors each ends up dying, until we see the last man standing—Ben, emerged cautiously from his secure space in the cellar of the farmhouse to find that police and other volunteers were roaming around, killing the zombies, and reclaiming their land for the safety of the living.

Unfortunately for Ben, these rescuers are less focused on finding survivors and more focused on mindlessly putting down anything they find that moves. While that might simply be interpreted as bad luck for our main character, Romero’s decision for this ending was actually fairly controversial considering the time in which it had been created. Now you might be asking yourself, where does the conversation of civil rights factor into this? Well, buckle up, buttercup—we’re just getting started.

Controversial Social Commentary

“Curiositas draws the viewer towards unbeautiful sights, such as a mangled corpse, and ‘because of this disease of curiosity monsters and anything out of the ordinary are put on show in our theatres,’” (Gunning, 124). Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) gives us these “unbeautiful sights” in spades. Consider the special effects that were available to directors at that time—the glimpses of a woman with her face eaten off at the top of the stairs and zombies ripping flesh off of bones after an unfortunate accidental explosion of the getaway vehicle were the literal encapsulation of this concept. The intangible concepts within this film are the reflections of society and how little progress has been made since 1968.

Freud pinpoints the appeal of the horror story. He begins by discussing the etymological root of the word “uncanny” in German, a word long associated with the horror genre, demonstrating how both the word and its opposite are very close in definition and usage… ‘it may be true that the uncanny [unheimlich] is something which is secretly familiar [heimlich-heimlisch], which has undergone repression and returned from it, and that everything is uncanny fulfills this condition.’ … Freud … hit upon the key to understanding the core of the horror genre. Horror is dissimilar from much of [the] science fiction genre in which the threatening ‘monster’ (often created because of the interference of science or technology)—whether it be alien, atomic mutant, or cyborg—is portrayed as the Other which must be destroyed or controlled by science, often in conjunction with the military/industrial complex, in order to save humanity. Horror tends rather to concentrate on another type of ‘Other,’ an ‘Other’ which is very familiar and because of that much more frightening, an ‘Other’ which is rooted in our psyche, in our fears and obsessions.

James Ursini, pg. 4 of the Introduction in The Horror Film Reader

The Civil Rights Movement

From 1954 to 1968 the Civil Rights Movement empowered Black Americans and their like-minded allies. They battled against systemic racism (or institutionalized racial discrimination), disenfranchisement, and racial segregation within the United States. The brave efforts of civil rights activists and innumerable protesters brought meaningful change to the US, through changes in legislation; these changes ended segregation, voter suppression for Black Americans, as well as discriminatory employment and housing practices.

The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

There were tragic consequences for two of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. With the assassination of Malcolm X on February 21, 1965, and the subsequent assassination of Civil Rights leader and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. Each of these losses to the movements provoked an emotionally-charged response; looting and riots put even more pressure on President Johnson to push through civil rights laws that still sat undecided.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968

The Fair Housing Act became law on April 11, 1968. It came just days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.; too little too late, but it prevented housing discrimination based on race, sex, national origin, and religion. It was also the last piece of legislation that was made into law during the civil rights era.

Casting a Black Actor in a Non-Ethnic Role

The way the lead character Ben was written originally with Rudy Ricci. Surprisingly, however, when 31-year-old African American actor Duane Jones auditioned for the part, the decision to cast him was unanimous. Even Rudy Ricci was on board with the change in plans, stating that, “Hey, this [was] the guy that should be Ben.”

Duane Jones—the Anti-Ben

Romero recalled that Jones had been the best option when it came to casting the part of Ben, and remarked that, “if there was a film with a black actor in it, it usually had a racial theme.” He even saw fit to mention that he resisted writing new dialogue for the part just because they had cast a black lead. It was assumed that Jones was the first black actor to be cast in a non-ethnic-specific starring role, but that barrier was broken by Sidney Poitier in 1965.

Interestingly enough, the role of Ben was supposed to be a gruff, crude, yet resourceful trucker. His essence was that of an uneducated or lower class person. On the other hand, Jones happened to be very well-educated, with fluency in several languages, obtained a B.A. at the University of Pittsburgh, and an M.A. at NYU. Jones was the one who flipped the script, improvising through the dialogue to portray his interpretation of Ben as a well-spoken, educated, and capable character. Therefore, as originally written, white Ben was a stereotype whereas Jones turned the character into the antithesis of a stereotypical black ben.

So why was Night of the Living Dead so controversial?

Even though Ben is the protagonist, he was never meant to be the hero—in fact, Ben was supposed to represent just an everyday Joe, who “simply reacted to an irrational situation with strong survival instincts and a competence that, though far from infallible, surpassed that of his five adult companions trapped in that zombie-besieged farmhouse,” (Kane). What we would expect in terms of racially heated arguments, we only witness the palpable tension that displays what goes unsaid. What also may not occur to modern viewers as being controversial, is the portrayal of a black man and a white woman being locked up alone in a house together. Segregation may have begun over a decade prior, but racism doesn’t die overnight just because laws are changed.

The “Final Guy”

The tragic ending of Night of the Living Dead was a commentary on real injustices that were happening at the time, as well as a foreshadowing of an issue that has doggedly limped into the systemic racism of the twenty-first century. The world was facing its end of days. The threat of the undead rising from their graves and feeding off of the living was enough to pull everyone together to stay alive—but racism was still alive and well. Unlike most of his African-American male successors of horror, Ben does not fall victim to the black character stereotype by being the first character to die. Ben makes it to the end—the so-called “final” guy—he was able to save himself when the house was overrun by the living dead. Then, after all of his hardship, he ends up dying at the hands of the gun-toting police officers.

Ben was wielding a gun, he was clearly not a revenant, and the sharpshooter who put one between Ben’s eyes could very obviously see this—his death affected not a soul in that situation, his life in plain language was unworthy of continuing in the eyes of the men who were supposed to serve and protect the living, who instead of seeing a human being, perceived a threat. The ending that Romero’s film allowed to linger in the minds of the audience was controversial because it made people think. It made them look at the social and political issues that were washing over the United States all around them; Romero delivered in that two minutes ending, a message that was unforgettable. It has thusly endured through the culture of horror and has continued to inspire modern horror cinema.

Final Thoughts

If classical Hollywood style is posited as the norm, then filmmaking practices that deviate from it risk becoming seen as “primitive” (such as early cinema) or “excessive” (such as genres where spectacle often seems to trump narrative, including musicals and horror films).

Adam Lowenstein, “Living Dead: Fearful Attractions of Film”

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

Interested in watching the full film now that you’ve read this article? Well, you’re in luck—this film is now in the public domain and can be watched online for free.

Work Cited

Gunning, Tom. “An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)Credulous Spectator.” Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film, by Linda Williams, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 1995, pp. 114–133.

Lowenstein, Adam. “Living Dead: Fearful Attractions of Film.” Representations, vol. 110, no. 1, 2010, pp. 105–128. JSTOR. Accessed 19 Jan. 2021.

Kane, Joe. “How Casting a Black Actor Changed ‘Night of the Living Dead’.” TheWrap, 1 Sept. 2010.

Harper, Stephen. “Bright Lights Film Journal: Night of the Living Dead.” Bright Lights Film Journal | Night of the Living Dead.

Ursini, James, and Curtis Harrington. “Introduction/Ghoulies and Ghosties.” The Horror Film Reader, by Alain Silver, Limelight Ed., 2006, pp. 3–19.

Georgia-based author and artist, Mary has been a horror aficionado since the mid-2000s. Originally a hobby artist and writer, she found her niche in the horror industry in late 2019 and hasn’t looked back since. Mary’s evolution into a horror expert allowed her to express herself truly for the first time in her life. Now, she prides herself on indulging in the stuff of nightmares.

Mary also moonlights as a content creator across multiple social media platforms—breaking down horror tropes on YouTube, as well as playing horror games and broadcasting live digital art sessions on Twitch.