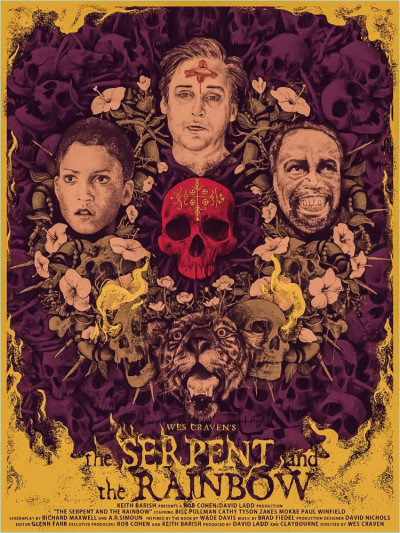

Even if you’ve never been buried alive, rest assured, this movie cannot hope to capture the terror that one must feel waking up to the darkness and heart-stopping fear of waking up in a coffin, with no possible hope of being rescued. If you have not yet seen The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988), then perhaps it’s time—this movie has aged well, at the time of this posting, it’s nearly thirty-two years old, still relevant and pretty terrifying through the right lens. Given the fact that this movie was created in the late eighties, it stands to reason that if it were remade, it could be given new life, it definitely has the potential with a higher-rated actor and better cinematography to be a more nail-biting journey to have a glimpse into what zombification in the voodoo culture is truly about. The Serpent and the Rainbow was based on a book with the same name and directed by Wes Craven—a highly regarded thrill-maker in his heyday—and is given the attribute of being inspired by a true story, which is believable considering the attention to detail that was paid to even the most insignificant aspects of the story.

“In the legends of voodoo

The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988)

The Serpent is a symbol of Earth.

The Rainbow is a symbol of Heaven.

Between the two, all creatures must live and die.

But because he has a soul

Man can be trapped in a terrible place

Where death is only the beginning.”

Set during the political unrest of Haiti in 1978, Dr. Dennis Alan (Bill Pullman), an anthropologist turned field-researcher has just come back from exploring for medicinal herbs and plants; he’s hailed as a hero at the biological research company, at which he works because he’s brought back medicines that no one before has ever been able to collect. No rest is given for the weary though and he’s immediately asked to go investigate the mysteries of zombification in Haiti—they have just come across evidence of a case eerily similar to that of real-life Clairvius Narcisse. Christophe was a man who died and was brought back to life. So, Dr. Alan sets off to find this mysterious zombification powder, something his bosses hope to find useful in their medical research.

Surprisingly, much of the lore of voodoo is represented quite faithfully, which has a lot to do with the fact that most of the movie was filmed on location during a time of political and social unrest; the scenes in which voodoo rituals occur, they were actually filming voodoo practitioners who were in a trance state. The authenticity of these scenes sets this movie apart from any other movie about voodoo that is out there, it can’t get more realistic than this without being an outright documentary. The whole movie was based loosely around The Serpent and the Rainbow (1985) a non-fiction book was written by Wade Davis. The author is to this day, an anthropologist who initially made himself famous by his research in the field of psychoactive plants; he was one of the first outsiders to gain access to the secrets of zombification and how the powder was created, which are highly guarded secrets in the community of voodoo in Haiti.

So, while simultaneously staying true to much of what voodoo is about and not intending to create a horror movie, director Wes Craven was somehow able to make the movie a psychological experience that kept it both interesting and entertaining, long enough to get to the meat and bones of the plot. Insights into the poorly staffed insane asylums and the psychological state of a person who had undergone the trauma of being drugged, declared dead, buried alive and then being dug up and made to serve a master, created an environment early in the movie that this entire expedition was going to be a dangerous one for Dr. Alan. Like a well-trained and eager anthropologist, our antagonist goes above and beyond what any sane field researcher would do, finding himself in graveyards searching for a mentally unstable resurrected Christophe, attending voodoo rituals in which he witnesses men chewing on fire and women eating glass, and running into an evil witch doctor, Peytraud, who does not want him to be successful in finding the secrets to zombification. It’s important to watch this movie without any lens of bias, as far as what valid religion and spiritual practice are, it requires people to be open to what is possible when belief in the strange and unnatural is strong and unwavering.

Possessing the knowledge that Wes Craven never intended this movie to be a horror flick, it’s quite easy to see past the dated effects and experience Dr. Alan’s nightmarish visions with the depth of fear that someone that has had the superstition of the land seeded into his brain. With an added element of complexity, Dr. Alan falls for the beautiful psychiatrist who aids him in his journey to the highly sought-after zombification powder, which allows him to be more easily manipulated by Peytraud who later has Dr. Alan in his clutches. The cinematography in the torture room of Peytraud is intense, especially considering the time in which the movie was made, the gore wasn’t a necessary element to induce fear in audiences. We know what is going to happen to our antagonist when we find him being strapped into a chair, with his underwear around his ankles, when Peytraud reveals a coffin nail and tells Dr. Alan that he wants to, “hear (him) scream.”

Not to be deterred, we see the effects that Peytraud has had to Dr. Alan’s mental state, his nightmares and visions get worse—he’s being buried alive in his dreams, he screams as blood begins to fill the coffin and quickly consumes his body. Political tactics are taken to scare Dr. Alan into leaving Haiti without what he came for, which nearly works if it weren’t for his hidden ally who ends up sneaking it to him after he has been forced into a plane that will take him home. Threats of being arrested and executed have been levied on him, which means he has to leave his lover, Marielle (Cathy Tyson), behind despite the danger she would be in for her associations with him. The brief time back in Boston is punctuated with the powder having been researched, which the movie is also incredibly true to its source, noting that the subject would be aware of everything that was going on, while still appearing clinically dead. Peytraud shows himself through magical means, making it clear that he can reach Dr. Alan wherever he may be—his visions have not ceased since arriving back home. Dr. Alan returns to Haiti in order to make sure Marielle is safe, he finds the ally that gave him the powder has been executed for what he has done—this is where things truly turn bad for him.

Don’t let them bury me. I’m not dead.

Dr. Alan – The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988)

After having zombie powder blown into his face by one of Peytraud’s associates, Dr, Alan stumbles through the village and eventually falls to the ground, pale and apparently dying–he utters the words that the movie is famous for, “Don’t let them bury me. I’m not dead.” The fear in his eyes is not overplayed, in fact, this part was incredibly well done. After being declared dead in the hospital, we see Peytraud has taken control of his body and is seeing to it that Dr. Alan is put in the grave.

“When you wake up, Dr. Alan—scream.

Peytraud – The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988)

Scream all you want, there is no escape from the grave.”

Before watching this movie, I read reviews of it, so this is always where I was led to believe that the movie ended—our hero, the noble anthropologist, seeking secrets for the future of medicine gets buried alive and that’s that—the ultimate fear of someone who is claustrophobic, meeting their demise in a cramped box with severely limited oxygen. Except, this isn’t where we end—Christophe, comes to Dr. Alan’s rescue when he awakens from his drug-induced trance and begins to scream. In a moment of unexpected vulnerability, Christophe consoles the anthropologist, “You’re alive. You see things the living can’t see. In a daring rescue of his lover, Dr. Alan squares off against Peytraud where he encounters several setbacks and finally overcomes the mind control of his nemesis, defeats the bad guy, rescues the girl, and saves the day. His visions cease and we’re led to believe that he goes on to live a happy and full life.

All in all, this movie has stayed relevant over the past three decades and is highly recommended for being both unique and authentic in its representation of zombies. You’ve got to check this one out!

Georgia-based author and artist, Mary has been a horror aficionado since the mid-2000s. Originally a hobby artist and writer, she found her niche in the horror industry in late 2019 and hasn’t looked back since. Mary’s evolution into a horror expert allowed her to express herself truly for the first time in her life. Now, she prides herself on indulging in the stuff of nightmares.

Mary also moonlights as a content creator across multiple social media platforms—breaking down horror tropes on YouTube, as well as playing horror games and broadcasting live digital art sessions on Twitch.