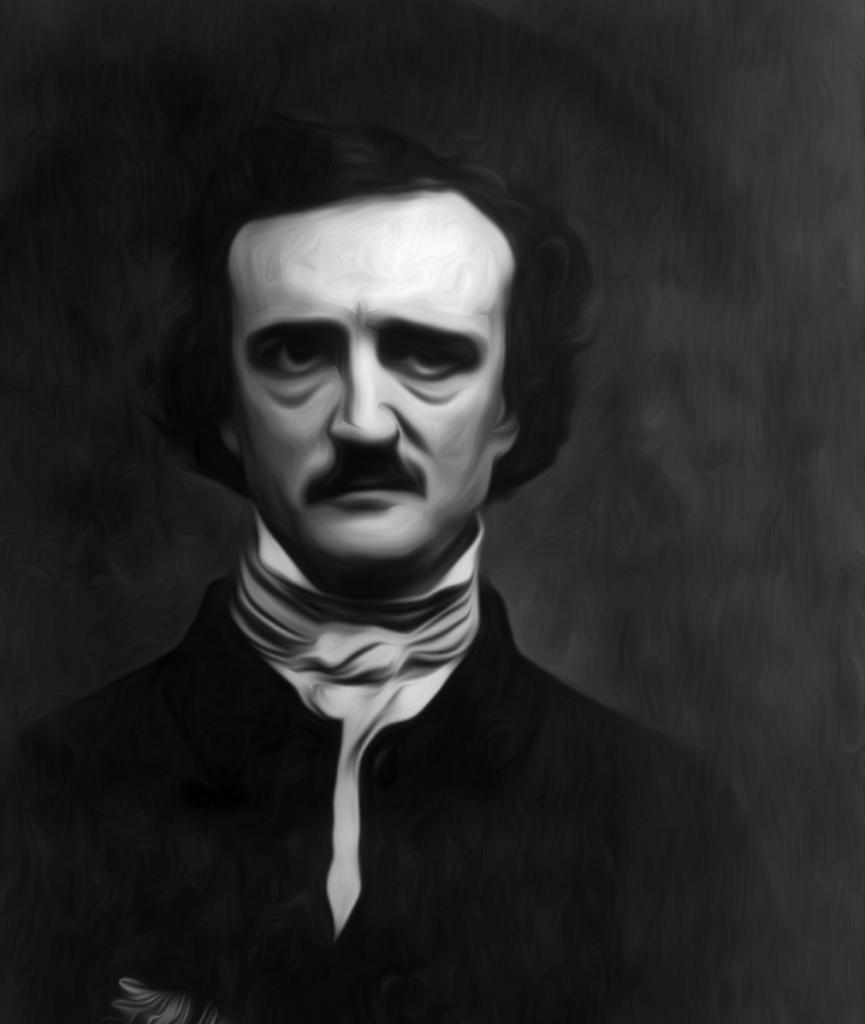

Dark and mysterious in life and in death, Edgar Allan Poe is most famous for the Gothic horror genre, was a master of macabre poetry and short stories that are the stuff of nightmares. As an American writer, he made a surprising number of enemies through his harsh literary critique of their work. His abundant well of imagination and creative abilities directly enabled him to create a new genre and he has long been considered the father of the modern detective story. While that alone is impressive enough, he is also often regarded in literary history as the architect of the modern short story. As a creative individual, he was also a principle forerunner of the Art for Art’s Sake movement within nineteenth-century European literature.

Edgar’s life, just like his profound short stories, is largely shrouded in mystery to this day. The substantial confusion between the facts and the falsehoods is a direct result of the blatant misrepresentation in a biographical piece written by one of his enemies—in an attempt to smear the dead author’s name. As a result of these widely distributed beliefs, Poe’s image has formed into one that is a morbid, macabre, and mysterious figure who dabbles and lurks in spooky cemeteries has contributed to his legend.

This horror icon grew to become such a renowned author due to his ingenious and profound stories, poems, and critical theories, which proved in time to be influential within their respective fields. He began to be the author everyone associated with tales of murderers and madmen, the prospect of being buried alive, and revenants returning from the dead. He is most widely known for poems like “The Raven,” “The Black Cat,” and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” but that’s not even close to the extent of his most famous works.

Poe managed to produce such compelling literature that he has remained in print since 1827. A man who led an incredibly dark and dreary life and somehow managed to produce these works of literary horror art that was consistently beautiful and haunting.

Early Life

Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 19, 1809; his parents were both traveling actors who Edgar was never able to truly get to know. His father was David Poe Jr. Who was originally from Baltimore, his mother Elizabeth Arnold Poe was British in descent. Both died before Poe was even three years old, while his father’s cause of death is unknown, we do know that his mother succumbed to tuberculosis which officially left Poe and his siblings as orphans. At that point, Poe was separated from his brother William and sister Rosalie and he alone was sent to live with John and Frances Allan—a successful tobacco merchant and his wife who lived in Richmond, Virginia. While Edgar seemed to develop a bond with Frances Valentine Allan, Poe’s relationship with John remained unsteady. Allan would never legally adopt his foster son Edgar, but he did send him to the best schools available where he was always a good student.

Despite butting heads, Allan raised Poe to be a Virginian gentleman, as well as a businessman; unfortunately for Allen, Poe was drawn to writing. By the time Poe was a mere thirteen years old, he was already a prolific poet, inspired by the British poet Lord Byron. Unfortunately for Poe, his efforts and literary talents were highly discouraged by his foster father and his headmaster at school. Since Allan raised Poe to be a businessman, he of course did not approve of the fact that Poe preferred to write poetry. He would also allegedly draft poetry on the back of some of Allan’s business papers—needless to say, this was frowned upon by Allan.

Adulthood

Education

Poe was admitted to the University of Virginia at Charlottesville in 1825, where he once again demonstrated his scholarly abilities. Unfortunately, a miserly John Allan sent Poe to his university with less than a third of the funds he would have needed to finish and he quickly accumulated debt. As a result, Poe turned to gambling to raise the money he needed to pay his expenses. By the end of his first term, Poe was rumored to have been so poor, that he had to burn his furniture to keep himself warm. This left him humiliated for being impoverished and furious with Allan for putting him in that position.

Forced to drop out of school, Poe returned to Richmond, Virginia where things went from bad to worse. When he arrived in Richmond, he went to visit his fiancée Sarah Elmira Royster, to the shocking discovery that she had become engaged to another man. After hearing this dismal news, a heartbroken Poe returned to Boston,

Military Service

Poe decided to join the U.S. Army in 1827, the same year he had published his first book—after serving for two years, Poe received news that Frances Allan, his foster mother, was dying of tuberculosis. Sadly, Frances passed away before Poe was able to return home to say his goodbyes. Heartbroken once more, he moved a few hostile months spent living with Allan drove him back to Baltimore to follow his dreams of writing, but also because he was able to call upon relatives for assistance. One cousin ended up robbing him blind, but fortunately for Poe, he met Maria Clemm, another relative who welcomed him with open arms and became a surrogate mother to him. In 1929, Poe was honorably discharged from the army, after having attained the rank of regimental sergeant major.

West Point Military Academy

Two years after meeting Clemm, he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point and continued to write and publish poetry. Poe once again demonstrated his ability to excel in any class but was thrown out after only eight months of attendance. It’s speculated that Poe intentionally got himself expelled to spite his foster father, by ignoring his duties and violating regulations.

In 1831, after moving to New York City, Poe published his third collection of poems, then to Baltimore to live with Clemm, before finally ending up back in Richmond, where the relationship between Poe and Allan had finally deteriorated.

Career

Poe began to follow his dream of being a writer when he published his first book Tamerlane (1927) at the age of eighteen. Later on, Poe was in Baltimore when his foster father passed away, leaving him completely out of the will and instead, witnessed an illegitimate child whom Allan had never met inherit everything. Poe was still living in poverty, but publishing his short stories when he could. One of these submissions won him a contest which was sponsored by the Saturday Visiter. Poe made valuable connections through winning this contest, which allowed him to publish more stories, and eventually, he grabbed an editorial position at the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond. This would be the first of several journals that Poe would direct over the following decade, through which he would rise in prominence as a critical writer within America.

While his writing continued to gain attention in the late 1830s and the early 1840s, his income from this work remained minimal and he was only able to truly support himself through his work editing Burton’s Gentleman Magazine and Graham’s Magazine in Philadelphia as well as the Broadway Journal in New York City.

Short Stories & Poetry

In 1935, Poe began to sell short stories to magazines—this was also when he began to establish himself as a poet—his best-known works and poems were made during these years, the years when he was happily married despite already being a depressed alcoholic.

Literary Critic

The Southern Literary Messenger was the magazine where he ultimately obtained his goal to become a magazine writer. Before a year had passed, Poe helped to make the Messenger the most popular magazine in the south—it was his sensational short stories and his absolutely ruthless book reviews. Poe ended up developing a reputation for being a ruthless critic who would not only attack an author’s work but also insult the author themselves as well as the northern literary establishment. This job led to Poe writing reviews that were meant to target some of the most famous authors in America—one of which was Rufus Griswold, the anthologist who would become Poe’s worst enemy in life and death!

Married to his Cousin

Clemm’s daughter, Virginia, began carrying letters to Poe’s love interest at the time, but soon after became the object of his desire. He began to devote his time and attention to her and when Poe finally moved back to Baltimore he brought both his aunt Clemm as well as his twelve-year-old cousin, Virginia. The couple was married in 1836 while she was still only thirteen and Poe was twenty-seven. The age difference, as well as the marrying of a cousin, was still considered a normal thing during this era, even though by modern standards, it would be inappropriate for a child to become a bride. The marriage proved to be a joyful one and it’s likely that it was one of the happiest times during his life, but finances were fairly tight throughout despite Poe’s gain in acclaim as a writer.

Taken by Tuberculosis

Virginia was tragically taken in 1947, at the young age of 24, which happened to be the age that Poe’s mother was when she also died of tuberculosis. Poe was devastated by Virginia’s death, so much so that he was unable to write for months—his critics assumed he would die soon after and they weren’t wrong. Yet, it’s also rumored that he became involved in a number of romantic affairs before he was engaged for the third time. This time to his original fiancée, Elmira Royster Shelton, who had recently become a widow just as Poe had become a widower.

Mysterious Death

While in preparation for his second marriage, Poe arrived in Baltimore in late September of 1849. He was discovered in a semi-conscious state on October 3 and was taken to a hospital. He ended up dying four days later of “acute congestion of the brain,” without regaining consciousness to explain what had happened to him during his last days on earth. Neither Poe’s mother-in-law Mrs. Clemm nor his fiancée Elmira knew what had become of him until they read about it in the papers. Medical practitioners later reopened his case and hypothesized that Poe could have been suffering from rabies at the time of his death, but the exact cause still remains a mystery.

Libelous Obituary

Only days after Poe’s death, one of his main literary rivals—he had several due to his moniker “The Tomahawk Man,” when he wrote his scathing literary reviews—Rufus Griswold, decided to write a libelous obituary about the dead author. This was done in a misguided attempt to get his revenge against Poe for some offensive things that Poe had written and said about him. Griswold attempted to smear Poe’s image by labeling him a drunken, womanizing, madman, who possessed neither morals nor friends; his hope was that these attacks on Poe would cause the public to dismiss his works and cause Poe to be forgotten completely. Unfortunately for Griswold, his libelous attack on Poe had the opposite effect on audiences and immediately caused the sales of Poe’s books to skyrocket, higher than they had ever been during his lifetime. The joke was truly on Griswold, however, who instead of being recognized as a writer is only recognized (if vaguely) as Poe’s first biographer, even if he intentionally botched the whole thing.

Work Cited

Edgar Allan Poe. (2020, September 03). Retrieved November 14, 2020, from https://www.biography.com/writer/edgar-allan-poe

“Edgar Allan Poe.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/edgar-allan-poe.

Poe’s Biography: Edgar Allan Poe Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2020, from https://www.poemuseum.org/poes-biography

Georgia-based author and artist, Mary has been a horror aficionado since the mid-2000s. Originally a hobby artist and writer, she found her niche in the horror industry in late 2019 and hasn’t looked back since. Mary’s evolution into a horror expert allowed her to express herself truly for the first time in her life. Now, she prides herself on indulging in the stuff of nightmares.

Mary also moonlights as a content creator across multiple social media platforms—breaking down horror tropes on YouTube, as well as playing horror games and broadcasting live digital art sessions on Twitch.