Found footage is a horror film subgenre that posits what the audience is watching is a “true” story that was filmed by “real” people. The recordings have been “discovered” and are presented as either the raw uncut movie, or they’re woven into a particular narrative that acts as an overarching story framework for the footage. Because the fictional crews are usually amateur filmmakers, the camera work is often shaky and unprofessional, the scenes tend to cut away during the action, the acting is very naturalistic, and commentary may be provided in real time during the filming.

Though it often crosses over into the domain of pseudo-documentaries or mockumentaries, this subgenre is set apart by its insistence on suspension of disbelief – the filming, the marketing, and the viewing experience all push the notion that what you’re seeing really happened. This is a subgenre that resides largely within the broader genre of horror as its techniques and tropes lend themselves well to horror. Indeed the “realness” of found footage films makes them that much scarier. Of course there are examples of found footage in other genres (Project X, Chronicle, District 9, Zero Day, and Earth to Echo to name a few), but the fact remains that the genre has been popularized by and largely populated with horror films.

It’s also interesting to note that there is a literary precursor to found footage in the form of epistolary literature and texts from the early 20th century. Both Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula are written as a series of letters and journal entries that have been discovered by a third party. Many of HP Lovecraft’s tales, such as The Call of Cthulhu, are also written as though they are real first-hand accounts being recounted in found documents and manuscripts.

Found Footage Horror Through the Decades

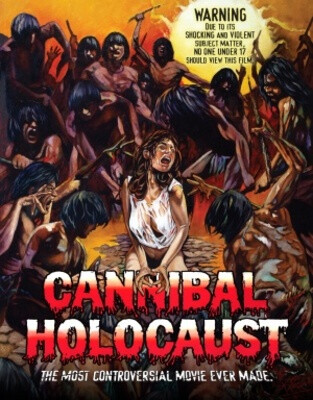

The origins of the found footage horror film can be traced back to a single, viscous little movie from the eighties that shocked the world, almost ruined the director, and gained a cult following. Cannibal Holocaust is about a rescue team who goes into the Amazon rainforest to search for a missing documentary crew. The lost crew was there to film the local cannibal tribes, and the rescue team comes across their film cans and the horrors that are recorded therein. Real indigenous tribes, a cast of amatuer actors, and actual animal deaths on screen, all added to the realism of the found footage style, making many audiences believe the events in the movie actually happened. The director was arrested on multiple obscenity and murder charges (the cast had to vouch for him in court) and the movie was banned in multiple countries.

The intense brutality, sexual violence, real animal killings, and grimy realism of Cannibal Holocaust almost sent the film to obscurity, but in the decades since its release it has become an icon of sorts in grindhouse and cannibal cinema, and its found footage style has influenced numerous directors and later movies. However, because of the movie’s general lack of appeal to mass audiences, its legacy as a pioneer in found footage filmmaking is often overshadowed by the more popular movies that came in later decades.

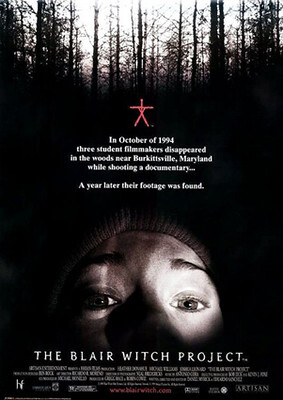

Though there are other examples of found footage movies from the eighties, the genre really exploded in popularity during the early 21st century. This resurgence is unequivocally thanks to the 1999 film The Blair Witch Project, which managed to break into the mainstream and pop culture in ways that were impossible for Cannibal Holocaust. Arriving in a sweet spot of amateur camcorder enthusiasts and the rise of the Internet, The Blair Witch Project capitalized on both of these aspects to immense success. The filmmakers recorded the film to look like a home movie and also incorporated a marketing campaign that included missing persons posters and a website detailing investigations into the case. All of this combined led to many people believing the movie was true found footage, and the film also became a landmark example of how financially lucrative a shoe-string budget movie could be.

Golden Era of Found Footage Horror Films

The early 2000s into the 2010s became the Golden Era of the genre as a slew of found footage films were released, many of them achieving both critical and financial success. The 2007 Spanish film REC received numerous awards and spawned several sequels. Another 2007 film, Paranormal Activity, broke box office records, stunning audiences, angering studio executives, and opening the gates wide for independent filmmakers to throw their hats in the ring. Cloverfield was released in 2008 and was praised for its viral marketing campaign and cinéma vérité style. Other popular films during this era include Lake Mungo (2010), Grave Encounters (2011), The Devil Inside (2012), V/H/S (2012), Creep (2014), The Taking of Deborah Logan (2014), and many more (plus all the sequels you could ever want).

Though the output of found footage movies has slowed down some in recent years, it’s clear that the genre still has some gas in the tank. For example, recent entries – such as Unfriended (2014), Unfriended: Dark Web (2018), and Host (2020) – are getting creative with technology to showcase their scares, utilizing elements like web chats and video calls. New means of storytelling mixed with the time-tested tropes of the genre leave us excited for the future of found footage in horror.

Ben’s love for horror began at a young age when he devoured books like the Goosebumps series and the various scary stories of Alvin Schwartz. Growing up he spent an unholy amount of time binge watching horror films and staying up till the early hours of the morning playing games like Resident Evil and Silent Hill. Since then his love for the genre has only increased, expanding to include all manner of subgenres and mediums. He firmly believes in the power of horror to create an imaginative space for exploring our connection to each other and the universe, but he also appreciates the pure entertainment of B movies and splatterpunk fiction.

Nowadays you can find Ben hustling his skills as a freelance writer and editor. When he’s not building his portfolio or spending time with his wife and two kids, he’s immersing himself in his reading and writing. Though he loves horror in all forms, he has a particular penchant for indie authors and publishers. He is a proud supporter of the horror community and spends much of his free time reviewing and promoting the books/comics you need to be reading right now!