Ever since the introduction of the Hays Code in 1927, films in the horror genre have fought to remain true to the voice of the genre. The consistency in which film creators have chipped away at those codes since their inception has brought us to where we are today; while movies like Hellraiser (1987) have still had to deal with censorship before they premiered, what is deemed excessive or exploitative is brought to new heights with each film that dares to push the limits.

Fully banned in Kansas…

When Frankenstein (1931) was first released, the local Kansas board banned it for the entire state; thousands of unhappy moviegoers wanted access, so eventually, the board relented. The Kansas board bastardized the movie with so many cuts that it, “would have stripped it of all its horrific elements,” which brought the intervention of the MPDDA and fewer cuts (Petley 132). The film standards that were enforced in the 1930s didn’t take into account the production of the horror genre; after wondering where the line would be drawn for a genre that consistently dug further into the dark, it was decided that:

As long as monsters refrained from illicit sexual activity, respected the clergy, and maintained silence on controversial political matters, they might walk with impunity where bad girls, gangsters, and radicals feared to tread.

(Cited in Petley 131)

Those standards wouldn’t last for long. The lines within horror are blurred, humans can be the monsters who don’t refrain from illicit sexual activity, demonic representations within films regularly disrespect the clergy, and have had a tendency to be outspoken on controversial political matters [see Night of the Living Dead (1968)]. Censorship for violent or graphic content was incredibly strict from the inception of the Hays Code until the 1960s when the standards for censorship were relaxed (Petley 130).

With the growing popularity of television sets in the home came tight restrictions for television programs. Televisions made entertainment easily accessible to people in the comfort of their own homes—this created stiff competition for filmmakers. While television standards were stricter, it allowed film production codes to be lowered in order to lure viewers back to the theater with the prospect of seeing something more forbidden. When Hellraiser was first released in 1987, audiences may have been a little shocked at the overt sexualization of pain and violence.

The graphic nature of the gruesome torture scenes cut in between scenes of sexual conquest and that starts within the first fifteen minutes. The mise-en-scène we are given with Julia’s flashback to her affair with her soon-to-be husband’s brother Frank sets the tone for the rest of the movie. Frank appears at the door, confident if not rude and slightly mysterious, drenched from the downpour of rain. He imposes himself upon Julia and we see her in her most innocent and unassuming form—cut to her walking into the third floor attic, a dusty, dingy, room in ill repair, to be alone with her thoughts.

Every inclusion of prop, from the knife that he cuts her nightgown strap with, to the wedding dress he lays her down upon to begin their torrid love affair, is essential to the story. Frank will take what he wants from Julia; having never been with a man who so confidently takes what he desires, Julia falls lustfully into their fervent and passionate, if not taboo, lovemaking. Engaging with Frank atop her pure white gown, sullying her presumable innocent reputation, is at the core of what Hellraiser translates to. Pleasure that feels sinful, Pain that feels pleasurable—two things that, with the Lament Configuration, blend together seamlessly.

The scene continues, cutting from the flashback of the affair to present-day Julia in longing remembrance, and then to her husband as he struggles to move a bed into their home. Frank and Julia climax in the flashback, Julia begins to cry, and Larry cuts himself deeply on a nail protruding from a wall. In these five minutes, we have excess in the taboo sexual act of cheating, the emotional show of Julia’s aching desire for Frank, and the adverse reaction Larry has to his own hand gushing blood. The movie continues on in this manner, unapologetic and all the more entertaining for it—we spend the next few minutes watching the floorboard soak up Larry’s blood and subsequently reconstitute most of Frank’s body.

Torture Porn and Erotica?

Some people might have found those two scenes to be subversive or even repulsive—some, according to movie critics at the time, found it comical. As if the excess pushed it from a horrifying experience, to a campy overdone joke. I think, when appreciated for the time it was created and given a little benefit of the doubt, it sows the seeds of a completely gratifying horror experience. Any attempt to relate to Julia, one might actually feel sorry for her—she feels as if she’s fallen in love with Frank and that he loves her back. The truth that she doesn’t really take into consideration is that desire and love don’t always coexist; Frank doesn’t actually care about Julia past using her for his own personal gain. We find out later, Frank’s coercive nature leads her to bring back men for him to feed off of and escape hell. Her own selfish desires lead her to assume that once he’s back in his skin (quite literally), they’ll rekindle their love-affair.

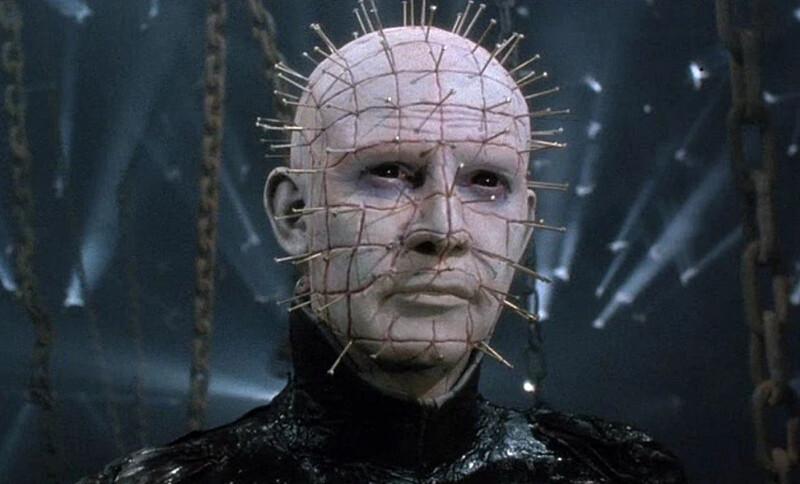

Violence and sex have had a tendency to be viewed differently in different countries. Where America has historically fallen back on christian outrage when it comes to depictions of sex (especially premarital sex) on the big screen, violence has been considered more acceptable. Alternatively, as Dumas has noted, countries like Sweden have had the opposite policy (29). People experience an incredible amount of shame and anxiety surrounding their own sexual desires that may or may not be considered taboo within an otherwise moral society—this of course causes an internal conflict for the audience (Dumas 29). What’s more is when Hellraiser’s Pinhead suggests that, “pleasure and pain (are) indistinguishable,” within his realm, it cements the concept of sexualizing brutality.

A certain morbid curiosity has escalated the gory nature of horror films with the release of each new feature. Post 9/11 audiences seemed to be even more desensitized than before—torture porn like Saw (2004) and Hostel (2005) hit the theaters—horror fans flocked to experience the repulsion and anxiety that comes with watching the suffering of others (Pinedo 345). A world where fear and uncertainty were becoming more commonplace, there became a vaccuum for horror. These gratuitous, taboo, excessive movies gave viewers a space in which we were free to be afraid.

Excess turns exploitative when the horror no longer fits around an underlying story, but instead, a story is made to fit around underlying ideas of violence and repulsion. Like pornography that attempts to have a plot—just look at any motion-picture porn parody—exploitative horror like The Human Centipede (2009), I Spit on Your Grave (2010), A Serbian Film (2010), and Tusk (2014) is simply an excuse to showcase gratuitous violence. These films are still liable to be heavily cut (Petley 146-147) and for good reason.

What is interesting is that such exploitative films are defended regularly, but are they films that need to be defended? A Serbian Film’s subject matter is indefensible, yet there are people who try to reason away the infant rape scene by bringing up that it wasn’t a real infant. Regardless of whether it’s a real infant or not, it’s meant to convey the scene in the most realistic way possible so as to instigate a severe repulsion response. It’s even suggested that “the masochistic and sadistic aspects of the film-viewing experience [implies] that viewers get some form of sexual gratification from these images,” (Pinedo 347) which in the case of A Serbian Film is beyond horrifying.

Horror and sex have a long, intertwined history, the eroticization of depictions of violence is nothing new. However, a horror film’s ability to stimulate viewers sexually, “not only draws their attention, but also primes them to react more strongly to other feelings, such as suspense and fear,” (Pinedo 347). In the end, what is considered exploitative or excessive is dependent upon the audience—there will always be those who object, just like there will always be those who call for more violence, gore, repulsion, and explicit sexual content.

Strong reactions and emotions have historically created experiences fewer people can forget. As an example, who can forget the release of Hostel in 2005, where viewers were not only fleeing the theater, they were reportedly throwing up in their seats. If the saying, “there’s no such thing as bad press,” is true—which it certainly seems to be within the horror genre—then these outrageous claims of such violent repulsion created a more morbidly curious audience.

Works Cited

Dumas, Chris. “Horror and Psychoanalysis: An Introductory Primer.” A Companion to the Horror Film, edited by Harry Benshoff, Wiley-Blackwell, 2017, pp. 21–37.

Petley, Julian. “Horror and the Censors.” A Companion to the Horror Film, edited by Harry Benshoff, Wiley-Blackwell, 2017, pp. 130–147.

Pinedo, Isabel C. “Torture Porn: 21st Century Horror.” A Companion to the Horror Film, edited by Harry Benshoff, Wiley-Blackwell, 2017, pp. 345–61.

Georgia-based author and artist, Mary has been a horror aficionado since the mid-2000s. Originally a hobby artist and writer, she found her niche in the horror industry in late 2019 and hasn’t looked back since. Mary’s evolution into a horror expert allowed her to express herself truly for the first time in her life. Now, she prides herself on indulging in the stuff of nightmares.

Mary also moonlights as a content creator across multiple social media platforms—breaking down horror tropes on YouTube, as well as playing horror games and broadcasting live digital art sessions on Twitch.