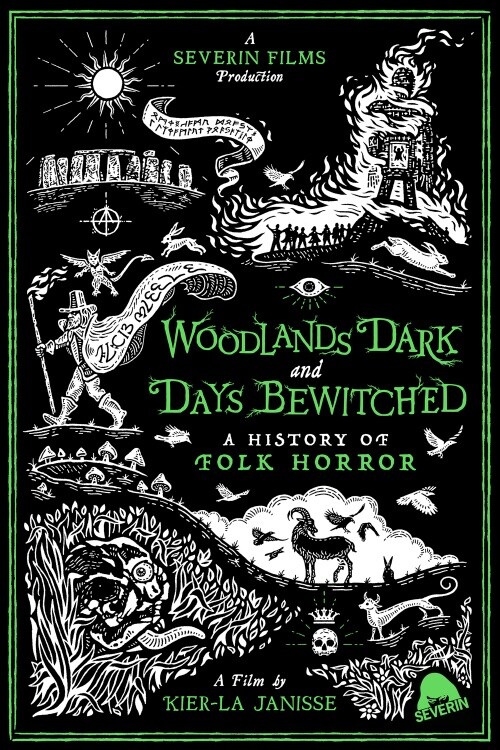

Defining the term “folk horror” and tracing its trajectory throughout history is somewhat of a Herculean task. For a term that sounds so simplistic, it is an incredibly complex and ever-expanding genre. Entire books have been written on the subject (such as Adam Scovell’s 2017 film criticism Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange), and there’s even a three hour long documentary about it titled Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror, which itself features over one hundred examples from film.

And while much of the emphasis surrounding the conversation is placed on British movies, there are plenty of overlapping examples in film, TV, and literature from around the world. Not to mention the actual elements that make up the genre are diverse, and range from folklore to the occult to witchcraft.

Simply put, it’s complicated.

To that end, this article is not going to be an exhaustive look at the genre (that’s what the books and documentaries are for), but rather a brief overview of the term, its tropes, and popular examples. Think of it as a primer; a starting place in the shallows of the vast ocean that is folk horror. Ready to wade in?

Origins of the Term

The British music scene experienced something of a folk revival in the 1960s, and that, coupled with the rise in Neopaganism, led to a general infatuation with and exploration of older belief systems. Bands like Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin explored occult themes in their songs, and the writings of famous occultist Aleister Crowley gained popularity. It wasn’t long before the fascination with folk and occult themes found its way into the world of cinema. And that’s not to say that music was the only vehicle for introducing folk horror, as disillusionment with modernism and outrage at governing bodies engendered in many a desire to return to nature and the simpler, older ways of life. At the same time, our post-industrial life has made us unused to rural life and uncomfortable with isolation.

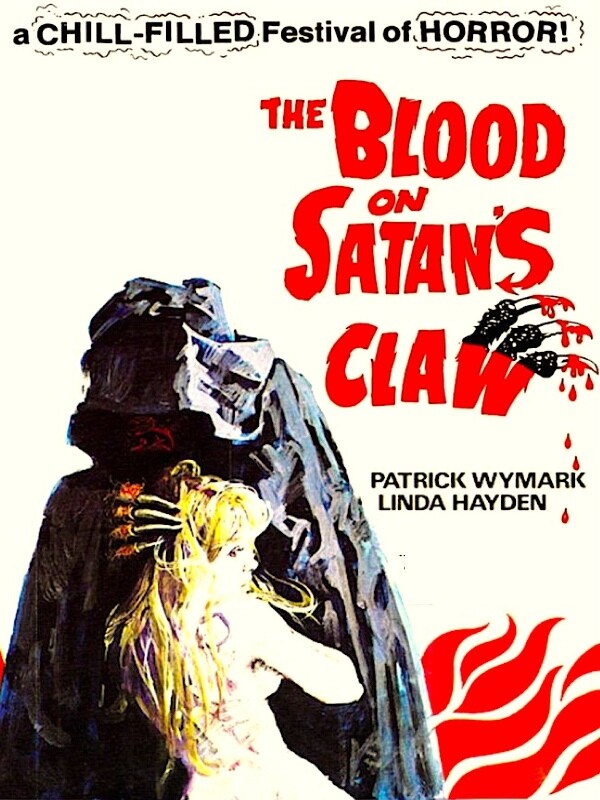

When cult classic The Blood on Satan’s Claws came out in 1971, the Kine Weekly referred to the film as “a study in folk horror”. The movie’s director Piers Haggard also used this term when describing his film. Later the term received renewed attention in 2010 when writer/actor Mark Gatiss interviewed Haggard during a section of the BBC documentary A History of Horror. These two moments, 1971 and 2010, appear to mark the emergence and then subsequent revitalization of the expression “folk horror”.

Elements of Folk Horror

Though it can be difficult to pin down the exact definition of folk horror, there is a general agreement that it is more of a mood, an atmosphere, than anything else. You know it when you see it, though it may be hard to explain why. Even common tropes can vary widely depending on geographic region and time period, and movies with very dissimilar plots can still fall under the folk horror umbrella. But for the purpose of simplicity, we will highlight what writer and filmmaker Adam Scovell (owner of the Celluloid Wicker Man blog) describes as the “Folk Horror Chain”, or the four basic thematic/aesthetic tenets of folk horror: Rural Location, Isolated Groups, Skewed Moral and Belief Systems, and Supernatural or Violent Happenings.

Rural Location: This was a big one for movies in the 60s and 70s because it saw a move away from filming in studios and out into the natural world. This element typically involves a fascination with pastoral landscapes and locations outside of urban life. Often there is an outsider who stumbles upon or is forced into a rural community, and who usually becomes some sort of scapegoat or sacrifice to traditional/pagan beliefs. Some argue that this element also encompasses ideas of psychography and location being a “state of mind” in more urban communities, such as in Roman Polanski’s film Rosemary’s Baby (1968).

Isolated Groups: This element typically takes one one of two meanings – either an individual is isolated from their normal physical environment or they’re isolated from those who share their same moral beliefs. For example, the characters in David Bruckner’s The Ritual (2017) find themselves stranded in the forest but also in discord with people who worship much different gods than they. This element is a link between the previous one and the next because isolation usually happens in rural environments, and it’s made even more upsetting because the antagonistic forces don’t act or think the same as the protagonist.

Skewed Moral and Belief Systems: In Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973), Sergeant Howie finds himself in a community whose religious beliefs and practices are at odds with his own. Across other examples there is a common thread of “modern” or “Christian” beliefs finding themselves in direct conflict with occult or pagan beliefs. This collision of morality and religious belief leads into or is specifically connected to the final element of the chain.

Supernatural or Violent Happenings: Folk horror stories are often steeped in, or at least influenced by, folklore of the particular region they’re set in, and this final piece of the chain usually involves either supernatural beings or some form of ritualistic violence (or both) related to that folklore. Invocations of demonic entities, horrific sacrifices, occult practices, and pagan idolatry are all par for the course.

British Folk Horror

The current popularity of folk horror, at least what our primary audience would be familiar with, owes a lot to British cinema, and in particular the Hammer Films production company. A group of films from the 60s and 70s, known affectionately as the “Unholy Trinity,” is what many point to as the birth of the genre. These movies are Witchfinder General (1968), the aforementioned Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and The Wicker Man (1973). These three films helped distinguish some common characteristics of folk horror, namely the picturesque landscapes, the isolated communities, and the emphasis on sacrifices and supernatural summonings. And yet, showing how intangible the genre is, these are also three very different movies in terms of plot.

Strong examples of the genre can also be found in British television from the same time period. There was the BBC’s Ghost Stories for Christmas series, which adapted several of M.R. James’s short stories with folk horror elements, such as Whistle and I’ll Come to You (1968), A Warning to the Curious (1972), and The Ash Tree (1975). There was a drama series from the BBC, titled Plays for Today, with standout hits like Robin Redbreast (1970) and Penda’s Fen (1974). And there were still other enduring examples of the genre like Children of the Stones (1977), a miniseries made for children but still incredibly terrifying.

Though the British rise in folk horror began in the 1960s and 1970s, there was something of a resurgence in the genre in the 2010s. Some of these newer British films (and in the UK more widely) took the tropes and themes from decades previous and put their own modern spin on them, while others sought to return to folk horror’s roots, so to speak, with their emphasis on ritual, folklore, and mankind’s connection to nature. While there are many examples to pull from – folk horror appears to be trending right now – several standout movies include David Keating’s Wake Wood (2009), Paul Wright’s For Those in Peril (2013), Elliot Goldner’s The Borderlands (2013), and Corin Hardy’s The Hallow (2015). Another prolific filmmaker in the genre is Ben Wheatley, whose canon of folk horror movies includes Kill List (2011), Sightseers (2012), A Field in England (2013), and In the Earth (2021).

Most of the common examples in British folk horror are from film, however there are many books from Britain that include plots and tropes from the genre. In fact, as it goes, some of the oldest examples of the genre are found in literature, from authors such as Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, and M.R. James. Some shining examples in more modern literature include Adam Nevill’s The Ritual (2011) and The Reddening (2019), Andrew Michael Hurley’s The Loney (2014) and Devil’s Day (2017), Thomas Olde Heuvelt’s Hex (2016), and Stephanie Ellis’s The Five Turns of the Wheel (2020) – as well as numerous comics, such as Simon Davis’s Thistlebone (2020) from 2000AD.

American Folk Horror

Though the term originated in the British imagination, the evolving genre of folk horror has set roots in American cinema and literature as well. In some cases this involves American filmmakers creating movies very much influenced by the British tradition, such as Avery Crounse’s Eyes of Fire (1983), Robert Eggers’s The Witch (2015), Gareth Evans’s Apostle (2018), and Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019). These films have strong similarities to their British cousins in regards to their emphasis on British landscapes and lore. The Blair Witch Project (1999) is another movie that could be included in this group, though it doesn’t fit the mold quite as well.

There are also many crossover elements between the genres of southern gothic and folk horror, and these commonalities can be seen in films such as Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter (1955). There is also a sub-genre of film called “hicksploitation” or “hillbilly horror” which spawns from the southern gothic tradition and which, upon first glance, may not seem to have much to do with folk horror. Yet, when one applies Scovell’s folk horror chain theory, the similarities begin to arise. Films that would fit in this category include movies like John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972), Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), and Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977).

In American literature, elements of folk horror can be seen as early as the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Washington Irving. Other popular novels and short stories in the genre include Thomas Tryon’s Harvest Home (1973), Stephen King’s “Children Of The Corn” (1977), Shirley Jackson’s “The Summer People” (1984), Raymond E. Feist’s Faerie Tale (1988), Elizabeth Hand’s Wylding Hall (2015), John Langan’s The Fisherman (2016), and Victor Lavalle’s The Changeling (2017).

A Genre Diverse and Divergent

As we continue to reevaluate and redefine what folk horror is, we begin to notice a few common truths: the genre has existed in some form or fashion long before the 60s and 70s, and some version of it can be found in almost every country around the world. Beowulf, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, early forms of mystical poetry, and even some of Shakespeare’s plays all have folk horror elements. The earliest example in film comes from the Danish-Swedish fictionalized documentary Häxan: Witchcraft Through The Ages (1922). Sweden has Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (1968). Australia has Peter Weir’s The Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975). Japan has Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba (1964) and Kuroneko (1968). And on and on it goes.

Also the more we explore the foundations and tenets of folk horror, the more we find examples which lie outside of the commonly accepted cannon, but which end up fitting the mold in diverse and interesting ways. Some titles here would include Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), Bernard Rose’s Candyman (1992), Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz (2007), Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017), Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018), and even the Paranormal Activity franchise.

As it should be clear by now, attempting to box the folk horror genre into an easy-to-digest definition is simply not possible. We didn’t even get into the various histories of folklore and dark fairy tales around the world and their individual influences and appearances in the genre. We also didn’t get into the overlapping traits in genres such as science fiction and cosmic horror. What we did accomplish, hopefully, is to give you a taste of the world that you will carry with you into your own exploration of this wonderfully diverse genre known as folk horror.

Ben’s love for horror began at a young age when he devoured books like the Goosebumps series and the various scary stories of Alvin Schwartz. Growing up he spent an unholy amount of time binge watching horror films and staying up till the early hours of the morning playing games like Resident Evil and Silent Hill. Since then his love for the genre has only increased, expanding to include all manner of subgenres and mediums. He firmly believes in the power of horror to create an imaginative space for exploring our connection to each other and the universe, but he also appreciates the pure entertainment of B movies and splatterpunk fiction.

Nowadays you can find Ben hustling his skills as a freelance writer and editor. When he’s not building his portfolio or spending time with his wife and two kids, he’s immersing himself in his reading and writing. Though he loves horror in all forms, he has a particular penchant for indie authors and publishers. He is a proud supporter of the horror community and spends much of his free time reviewing and promoting the books/comics you need to be reading right now!