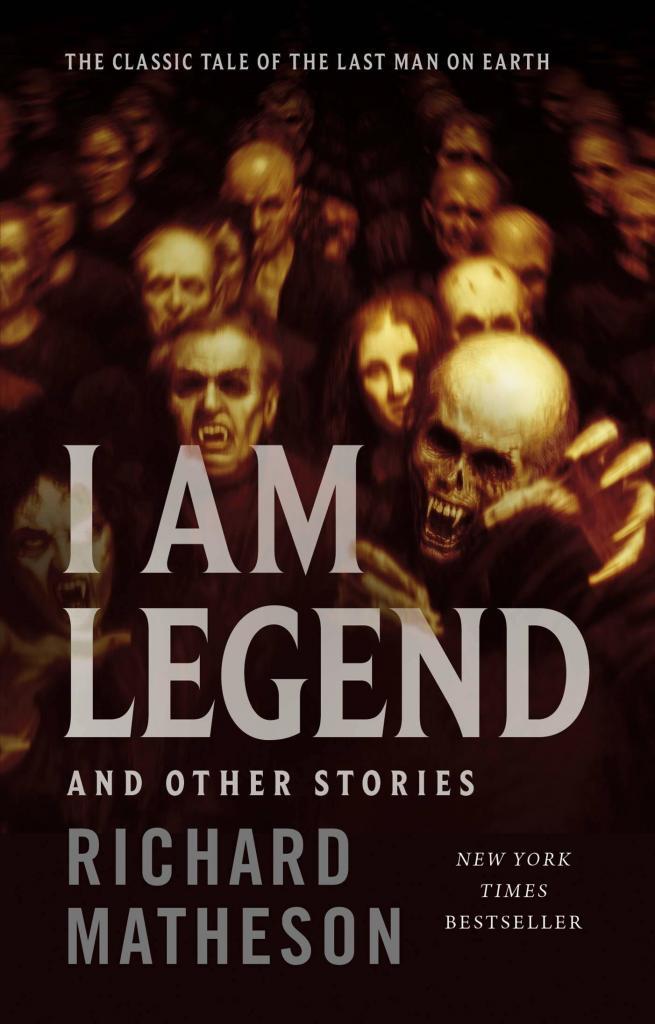

It happens so often within horror culture that we become familiar with a cinematic franchise that has been based on the original work of a talented writer whose life’s work revolves around their creativity. When it comes down to it, hit movies, such as I Am Legend (2007), are born from books that we are generally unaware of. Kind of crazy, right? One such famous author that you probably have never heard of, is Richard Matheson–after career that spanned nearly seven decades, he passed away in 2013 as a bestselling author as recognized by The New York Times for works such as I Am Legend (1954), Hell House (1971), Somewhere in Time (1975), The Incredible Shrinking Man (1956), and many others. He has been cited by Stephen King as being the biggest influence on his own work, but he has also brought the spine-tingling fear into the lives of his fans.

[Matheson is] the author who influenced me most as a writer.”

– Stephen King

Recognized and appreciated by some enormously famous modern authors and stars of their own right, Richard Matheson was named a Grand Master of Horror by the World Horror Convention and even received the Bram Stoker Award for Lifetime Achievement. Other notable times where he was recognized as a writer, was when he won the Edgar, The Spur, the Writer’s Guild Awards–and just three years before his death, he was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame. Unsurprisingly, a legend of his quality was also a writer of several screenplays for movies and television series–his most famous job in this respect was as a contributing writer to the original The Twilight Zone.

Richard Matheson’s ironic and iconic imagination created seminal science-fiction stories . . . For me, he is in the same category as Bradbury and Asimov.

– Steven Spielberg

The Literature of Matheson

Since the first Matheson story was published in 1950, nearly every major writer of science fiction, horror, and fantasy has derived some type of inspiration from him–Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, Peter Straub, and Joe Hill are amongst the most renowned writers. He revolutionized the gothic horror genre that was imagined initially by Bram Stoker and removed it from the traditional Gothic castles and strange otherworldly settings to the modern, more realistic world that we can better associate with. Along with the change of setting, Matheson allows the supernatural, paranormal, and dark examination of the human soul to permeate his stories. What’s more, is Matheson also somehow brought in the existential dread that made the cosmic horror genre so captivating.

Matheson’s first actual novel, Hunger and Thirst (2000), actually went unpublished for several decades, while it was ready in 1950 his published told him that it was much too long for publication–so it sat in his desk for fifty years.

So what exactly did Matheson write that we’ve heard of, even if we haven’t heard of him? Well–we named a couple of them above, but here are a few in more depth, we’re sure you’ll be familiar with at least some of these.

He was a giant, and YOU KNOW HIS STORIES, even if you think you don’t.

– Neil Gaiman

I Am Legend (1954)

Set in the future of 1976, the year after a deadly plague has swept the world and killed nearly every human being on earth–after dying, the world’s humans rise from the grave as vampires–sensitive to light, garlic, and mirrors. Since they are dormant during the day and impervious to bullets, Robert Neville, the one remaining human, has managed to survive by fortifying himself in his house at night and slaying vampires by day. Over time he begins to experiment on the vampires, he kidnaps them while they’re sleeping and begins to see how they react to different stimuli. We see the stereotypes of vampire lore challenged here, including when Neville begins to work on isolating the vampire germ.

The moral of the story is that sometimes the monsters are who we least expect them to be.

Hell House (1971)

Four people–a physicist, his wife and two mediums–have been hired by a dying millionaire to investigate the possibility of life after death with only a week to investigate the infamous Belasco House in Maine, which is regarded as the most haunted house in the world. The Belasco House has been thusly dubbed as “Hell House” due to the horrible acts of blasphemy and perversion that occurred there under the influence of Emeric Belasco. Murder mystery, as well as the puzzle of why the majority of people who enter Hell House end up dead before they can leave, make up the spiraling tale of Matheson’s Hell House.

Nightmare at 20,000 Feet from the anthology Alone by Night (1961)

Often hailed as one of Matheson’s best-known works, Nightmare at 20,000 Feet is the tale of an airline passenger who experiences feelings of insanity–to the point of doubting whether or not he was seeing reality when only he sees a gremlin on the wing of the plane, damaging one of the engines.

This short story debuted in the anthology Alone by Night (1961) and has been reprinted numerous times–it has even been realized on both the original series of The Twilight Zone as well as the more modern reboot as well as inspiring several scenes in other television shows.

A Stir of Echoes (1958)

A typical and ordinary life is something that Tom Wallace takes advantage of without realizing it–he scoffs at the idea that there is anything more to the world than what meets the eye, that is until by random chance an event awakens the psychic abilities that he never could have imagined possessing. Tom’s existence turns into a waking nightmare as he begins hearing the private thoughts of the people who surround him on a daily basis and he learns secrets that he never wanted to know. Eventually things escalate to the point where Tom begins to receive messages from beyond the grave.

As can be seen within the body of work of Richard Matheson, we see the trademark characters that he developed, one of which is the solitary, bewildered man.

Now that author Richard Matheson has passed away, it’s wonderful to be able to hear his own words directly from the horse’s mouth.

Georgia-based author and artist, Mary has been a horror aficionado since the mid-2000s. Originally a hobby artist and writer, she found her niche in the horror industry in late 2019 and hasn’t looked back since. Mary’s evolution into a horror expert allowed her to express herself truly for the first time in her life. Now, she prides herself on indulging in the stuff of nightmares.

Mary also moonlights as a content creator across multiple social media platforms—breaking down horror tropes on YouTube, as well as playing horror games and broadcasting live digital art sessions on Twitch.