It’s not difficult to find sources about the Cropsey Maniac—that is if you’re looking for what has overwhelmingly taken the place of the original urban legend. Finding an article that doesn’t devolve into a true crime tell-all about Andre Rand and the serial kidnappings and assumed murders of disabled children from Staten Island is difficult, if not outright impossible. In fact, we’ve even addressed the true crime events here, but only in juxtaposition to the original, forgotten origins of the Cropsey Maniac urban legend.

The Origin of Cropsey

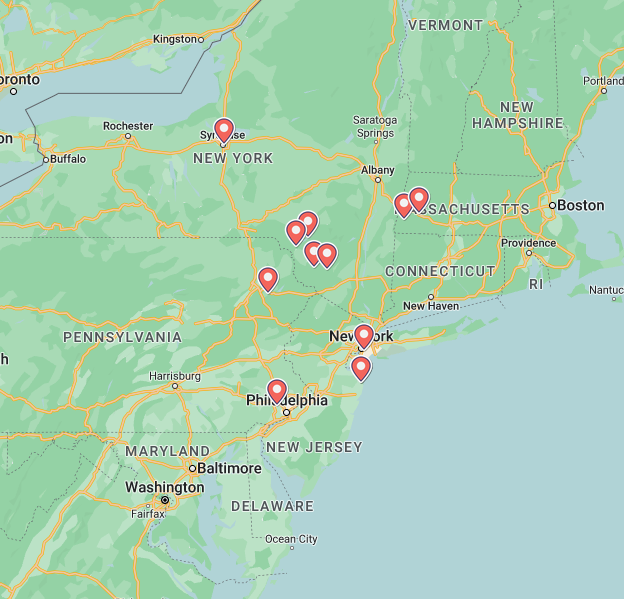

In 1977 the New York Folklore Society published an article that detailed some of the varied accounts of the Cropsey legend, from a survey of eleven New York City informants which Breslerman conducted in the fall of 1966 (Haring 16). What Breslerman found in his survey was, was that while all of the accounts varied on specific details, all of the significant plot events went relatively unchanged.

As a time-honored tradition of summer camps in New York and some surrounding regions, children would attend bonfires to hear the story of the Cropsey Maniac. Once a well-respected member of the community, the accidental death of a loved one sparks a homicidal madness in him and drives him to stalk and kill children who stray off the grounds of the camp. Below is one of the accounts in full, from Peter Sherman, who was identified as a former camper and counselor at Camp Lakota on Masten Lake in Wurtsboro, New York.

George Cropsey was a judge. He had a wife and two children, all of whom he loved very much. He owned a small summer cottage along the shores of Masten Lake. His wife and children would go there for the summer months, and he would come up to visit with them on the weekends… One night two campers snuck away from the camp’s secluded evening activity and went down to the lake to roast some marshmallows. The fire they built went out of control and there was a big fire on the lake. George Cropsey’s family was burnt to death. When Cropsey read the report in the newspaper, it is said he became completely white and disappeared from his home. Two weeks later one of the campers from Lakota was found near the lake chopped to death wtih an ax. There was talk of closing the camp for the remained of the summer but they didn’t.

The camp owners insisted upon constant supervision of the campers, there were state troopers posted in the area, and each counselor slept with either a knife, an ax, or a rifle. One night at about three in the morning, one of the counselors was awakened by the screams of one of his campers. He put a flashlight in the direction of the screams and saw his camper bleeding to death, and, standing over him, a man with chalk-white hair, red, bloodshot eyes, and swinging a long, bloody ax. When the maniac saw the light, he ran from the bunk, but the counselor chopped at his leg with the hatchet he was armed with. The man got away but left a trail of blood into the woods. The state troopers were called, and followed the trail into the woods. They called to Cropsey to surrender, but all they heard was crazed laughter. They determined his position, and when he would not give himself up, they built a circle of fire around him. When the fire had subsided, they searched the woods for his remains but could find nothing. The police closed the file on Georg Cropsey, assuming him to be dead…

It is said that on the evening of the anniversary of the death of Judge Cropsey’s family, you can see the shadow of a man limping along the shores of Masten Lake.

(Haring 15-16)

Significant variations of the Cropsey Legend

Summer camps weren’t the only locations where these stories were told. Boy Scout circles, summer jobs, middle schools, high schools, and even universities were hot spots for spooky storytelling. Regardless of where the informant heard the story, their version was always localized to their respective camp or school.

Whether George Cropsey was the owner of a hardware store, a member of the city council, a county judge, or a retired businessman, he always seemed to be one of the best-liked men in town. In each story, he has a wife and at least one child who suffers an accidental death. Of course, it’s a tragedy and Mrs. Cropsey suffers immense sorrow—in most if not all cases, she dies from her grief not too long after her child.

In some instances, Cropsey’s wife and child(ren) die together in a fire or some other inexplicable accident. George Cropsey goes silently mad, disappears and that’s when campers start to go missing or turn up dead. When the police got involved, they would sometimes involve local residents organized into search parties. They would comb forests and even drag the nearest lake in an attempt to locate the missing children.

The terror continues as more campers and counselors go missing, or camp dorms go up in flames—Cropsey takes his revenge upon the innocent souls he deemed responsible for the misfortune that befell his family. The authorities realize that it is George Cropsey perpetrating all of these heinous acts against the youth and a manhunt begins.

In most stories, Cropsey is somehow cornered—whether by a fire in the forest, by bullet holes penetrating the boat he’s escaping in, or by chance of him plunging to his death off of a cliff. It is believed that he died, although there was no indisputable evidence, or body found to conclude that he was, in fact, dead. In every story, after his supposed death there is still a lingering suspicion that he is still out there, waiting to continue his murderous rampage. Overall the endings of each of the versions Breslerman acquired, the motif of the death of children as punishment remains the same.

This background story shows campers that an average person, who would usually be trusted in a city setting, may not be trusted in unfamiliar places. This shows the uncertainty of what might lurk in nature and serves as a warning away from the unknown.

(Vale 3)

Cropsey Pop Culture Parallels

When The Burning came out in 1981 it wasn’t particularly well received—especially not in comparison to the other slashers of the time, but it has since become something of a cult classic. Never mind the period-appropriate stunts, special effects, and over-the-top acting, this movie was loosely based on the original New York urban legend.

The film follows Cropsey, the abusive alcoholic caretaker of Camp Blackfoot; the counselors decide that pranking him will be the sweetest revenge. When their plan goes more terribly than they could have possibly expected, it ends with Cropsey being engulfed in flame, recovering in the burn unit of the hospital, and Camp Blackfoot being shut down.

The ill-fated prank spurs the beginning of a hunt for revenge, years later, against the counselors and campers of the local Camp Stonewater. Like other slashers of the time, the killings primarily surround the horniest of teenagers, leaving everyone else as victims of circumstance and convenience. Not precisely a blow-for-blow telling of the original legend, but it ultimately pays homage to it in ways that count.

Where the Cropsey Urban Legend Meets Reality: An Evolution to a Chilling True Crime Story

Cultures around the world have practiced the tradition of oral storytelling, mainly as fables and folklore for younger generations to learn an important lesson. This tradition would relate chilling tales to children about what could happen if they didn’t listen to their elders.

The community of Staten Island was no different in the mid to late twentieth century. When they would tell the story of the Cropsey maniac it was meant to warn them about the hidden dangers of the world and a feeble attempt to keep teenagers from misbehaving.

After all, Staten Island may have turned into a suburban community, but it was originally established as a dumping ground—not only for local garbage, but was also rumored to be a hot spot for mob body dumps.

My search for source material on this legend was originally quite thin; I was searching for the legend, the myth, and the fiction. My misfortune was that I consistently hit the same wall—with stories about the “real” Cropsey, which is what Staten Island locals dubbed Andre Rand, a convicted kidnapper, and suspected serial killer.

For the kids in our neighborhood, Cropsey was an escaped mental patient who lived in the tunnels beneath the old, abandoned Willowbrook mental institution. Who would come out late at night and snatch children off the streets.

Joshua Zeman, Cropsey (2009)

The origin story of Cropsey is often confused with the real-life tragedy that befell the Staten Island community in that surrounded the Willowbrook State School grounds. It’s not surprising that the story of Cropsey was linked to a devastating series kidnappings and subsequent killings. Afterall, there were striking similarities between the spooky story told over a summer camp bonfire and the man who later embodied the legend.

… as teenagers we assumed Cropsey was just an urban legend. A cautionary tale used to keep us out of those buildings and to stop us from doing all those things that teenagers like to do, but all that changed the summer little Jennifer disappeared. That was the summer all the kids from Staten Island discovered that their urban legend was real.

Joshua Zeman, Cropsey (2009)

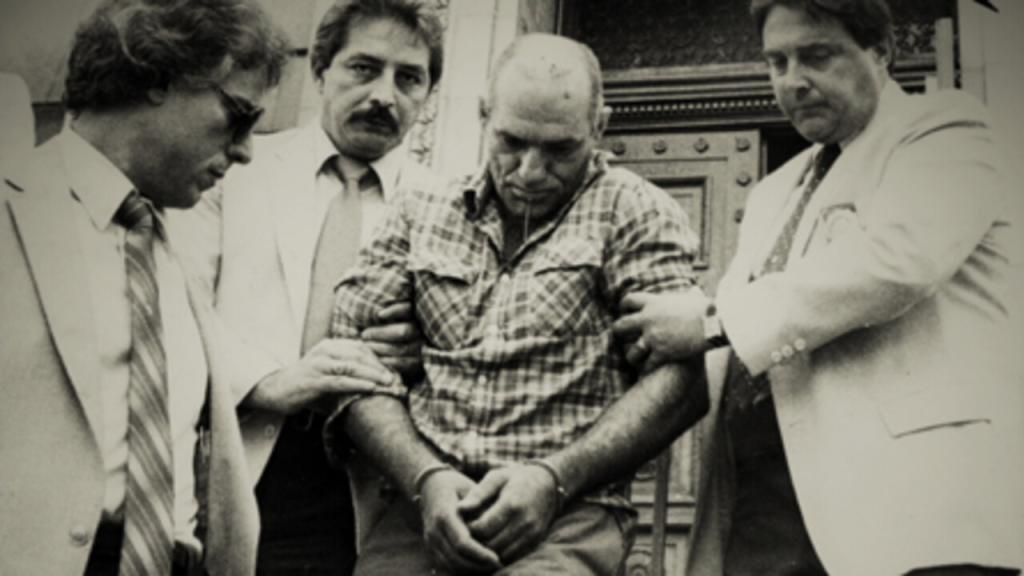

Andre Rand became the boogeyman of Staten Island, but he allegedly started out as an employee of Willowbrook State School. In some instances, he’s said to have been an orderly and in others a lowly janitor—these two accounts don’t seem to line up at all and we found no sources to cite in this instance.

After his brief two years of employment at the Willowbrook State School, Rand didn’t leave the area, instead, he set up his own private shantytown and remained on the grounds of the school. Rand was allegedly seen with several of the victims before their disappearances which ultimately made him a suspect.

One of the girls was found buried in a shallow grave between 150-200 yards from where Rand’s campsite was located. There was a trial, but Rand was only able to be convicted on one charge of first-degree kidnapping, but the jury was unable to convict him of the murder charge, despite his proximity to her grave. Rand, who is currently serving two 25-years to life sentences will be eligible for parole in 2037.

Did you know all of this about the Cropsey Maniac? If not, what did you know about the legend? Where were you when you heard it and what age were you? Let us know in the comments below!

Sources

Cropsey. Directed by Joshua Zeman and Barbara Brancaccio. Breaking Glass Pictures, 2009.

Haring, Lee and Mark Breslerman. The Cropsey Maniac. New York Folklore 3. 1977 Pp 15-27.

The Burning. Directed by Tony Maylam, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1981.Vale, Meredith. The Cropsey Maniac. Artifacts Journal 11. 2014 Pp 1-5.

Georgia-based author and artist, Mary has been a horror aficionado since the mid-2000s. Originally a hobby artist and writer, she found her niche in the horror industry in late 2019 and hasn’t looked back since. Mary’s evolution into a horror expert allowed her to express herself truly for the first time in her life. Now, she prides herself on indulging in the stuff of nightmares.

Mary also moonlights as a content creator across multiple social media platforms—breaking down horror tropes on YouTube, as well as playing horror games and broadcasting live digital art sessions on Twitch.